The ending of Spirited Away is densely packed — even for a Miyazaki film ending. (Looking at you, Howl.)

Japanese animated films often have short, swift endings where a lot of storylines can be wrapped up in a dizzyingly short timeframe.

This tendency is especially true for creators as well-versed in traditional Japanese storytelling structure as Miyazaki is.

No wonder that endings of anime are a significant entry on the list of things that baffle Western critics (and viewers) of Japanese animation.

Hayao Miyazaki is a master of the swift storyline wrap-up (among the many other things he’s the master of), and he seems to open more and more storylines with each new film — and who knows, maybe he’s doing it partly just to see how many he can fit in and resolve in a single film.

Whatever the reason, it’s clear that the later the Miyazaki film, the more balls it keeps in the air at any one time, and when you add up the number of elements making up Spirited Away’s end sequence, there’s a lot.

From the point that Chihiro steps out of Zeniba’s cabin, we witness:

- Chihiro and Haku’s reunion,

- Kaonashi’s character wrap-up,

- Chihiro reconnecting with her early childhood memory,

- Haku’s true identity revealed,

- Chihiro’s final test and release from her work contract,

- Boh’s character development, Yuubaba’s character development and Haku’s character development all covered in a couple lines of dialogue each,

- the fate of Chihiro’s parents resolved,

- Chihiro’s farewell to Haku,

- her reunion with her parents and the trek back to our world,

- taking a last glimpse of the tunnel,

- and finally starting off towards her new life, having learnt her lessons from the film.

If you think back to your last viewing of the film, how long would you say these 14 different bits of plot resolution take up of the 2-hour runtime?

20 minutes? 15? 12?

Nope — it’s a whopping 7 minutes.

That’s the patented Miyazaki Storytelling Density™ at work, y’all.

Each of these elements is interesting on their own and I want to eventually cover them all on this blog. But for now, there’s one specific element I want to focus on.

It holds huge mythological importance, ties into many things outside of the film, and reveals a lot about how Miyazaki thinks of storytelling as well as adapting old myths for a modern age.

And I start with this topic as it came in the form of question from Reham, who sent it in to the Moon Rabbit Hotline. Here’s her question:

“Hi Adam, I wondered about the end of Spirited Away. In your opinion, why would Haku tell Chihiro not to turn around when she’s about to leave to her family? Thank you.”

I love this question because it points to a very interesting tiny detail that, in turn, contains a lot of thought and a lot of background to unpack.

I originally sat down to write a simple straightforward answer to this, but ended up down many a rabbit hole.

So today, let’s follow the moon rabbit on a tour of ancient myths from Greece through the Middle East to India before returning to Japan to connect ancient and modern and see how a millenia-old storytelling element is turned upside down — and why.

A long history of ‘Don’t look back’

As anyone who’s seen even just one Miyazaki film knows two things:

- He’s well-versed in various mythological systems from around the world, and

- He loves putting in mythical elements that are shared across several cultures throughout history.

(By the way, #2 is one of the reasons why Ghibli films resonate so well with audiences outside of Japan, even though these films are conceived with Japanese audiences in mind.)

Asking someone not to look back as they leave a place is a very specific motif that comes up in a number of mythological stories quite separate from each other, from Orpheus going to get Eurydice from the Ancient Greek underworld, to Izanagi going to get Izanami from the underworld in Japanese creation mythology, to Lot’s family being told not to look back at the city of Sodom as they flee in the book of Genesis in the Old Testament.

So you can see that’s already quite a wide-ranging array of cultures that this exact request of “don’t look back” pops up, even if the circumstances and outcomes are different in each story.

Trials of initiation

The stories of Izanagi & Izanami, Orpheus & Eurydice, and Lot & his wife all belong to the “trials of initiation” story type, which simply means that the hero of the story has to undergo a trial.

The hero can pass the trial and gain something: a quest reward, an acceptance into a group, a spiritual experience or knowledge.

They can also fail the trial and face dire consequences: lose the ability to reach their goal, get booted out of the mystical place they were in or, in some cases, die. Hero quests are not without risk!

One of the most known, slightly related, initiation failure storyline is in the Ancient Sumerian epic of Gilgamesh, where Gilgamesh is not told to not look back but is told instead not to go to sleep. It sounds easy, so he takes the challenge.

Long story short, he does fall asleep and loses his chance at immortality — a quest he also embarked on because of the death of a loved one, like Orpheus and Izanagi.

Interestingly, in each of the “don’t look back” trials I mentioned above, at least one character fails the test:

- Lot’s wife turns around to look back at the destruction of Sodom — and turns into a pillar of salt.

- Orpheus looks back immediately when leaving the underworld to see if Eurydice was indeed following him — and loses the chance of being reunited.

- Izanagi looks at Izanami because he doesn’t want to accept that his wife now belongs to the underworld (although in this story there was no quest condition that would have actually led to Izanagi getting Izanami back to life).

The “one direction” rule

The key to understanding these stories and their relation to the modern example of Spirited Away is that all of the stories above have an element of directionality: the heroes are going in one direction, and there’s another direction that is forbidden.

This bit is shared with other types of stories that don’t have the explicit “don’t look back” trope show up, so may give us close to what these stories hint at as meaning.

In one Hindu mythological story, death god Yama takes young prince Satyavan’s soul as part of a prophecy foretelling his early death. However, Satyavan’s holy-level devoted wife Savitri basically goes “yeah, how about no”.

Even for Death, there is one rule: Yama must not turn back when he’s transporting someone to the realm of the dead. Yama knows this. Savitri knows this — but she’s also adamant.

So Savitri follows Yama into the underworld, pestering him with praise and philosophical insights and eventually wearing him down with some how-to-fool-the-genie-into-giving-you-more-wishes type logic. This makes Yama turn back, giving Savitri a chance to retrieve her husband’s soul.

In this story, there is no explicit trial — but there is the same directionality. Here it’s the death god who is defeated and so it is he who must turn back, away from the direction of the underworld, and towards the direction of the living, granting life.

The meaning of looking-back tests

I personally think these initiation trials are about spiritual resolve.

Can you go based on trust and do the thing you need to do, or will you be bogged down and succumb to the power of human emotion? Can you be in control of your desires or will your desires take over?

The few who win this kind of test, like Savitri, do so because they’re so holy they are way beyond earthly desire and their attachment is so pure that even gods can’t disagree with them.

In the more common poetic/melancholic stories have the heroes fail, and by doing so they ultimately reveal the humanity of these characters and that it’s hard as a human being not to form an attachment to other people, or to our home — which makes me think of Lot’s wife’s punishment as a bit harsh by today’s standards.

But it’s also to do with whether we can acknowledge the directionality principle in our lives: that while we’re free to move about in space, the same is not true for time. We cannot turn back time, and we cannot go back to the past. Apart from some very rare cases, motion goes one way.

In this sense, one possible moral shared by these stories is that forming too strong of an emotional attachment to the past will make us lose our focus in life, depriving ourselves from a connection with our present and the ability to build a future.

Spirited Away and the mythological underworld

So how does this all tie into Spirited Away?

Well, Spirited Away specifically and deliberately evokes these stories, and because of that, we can draw parallels between what happens in the original stories versus what changes Miyazaki makes when he builds his own story.

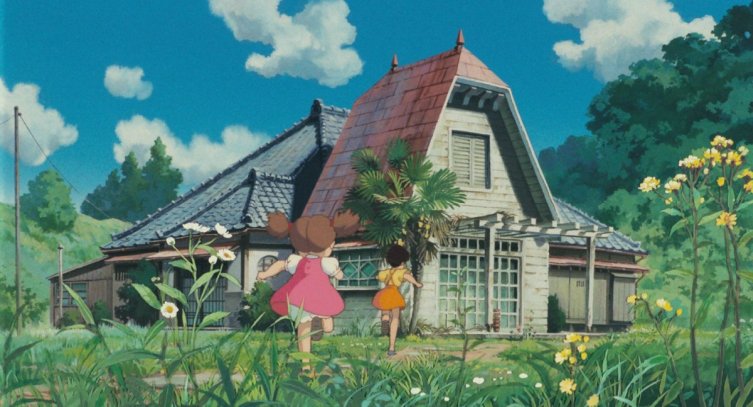

The film’s beginning, very much a callback to My Neighbor Totoro’s first scene, finds the main character already on a journey – in a moving vehicle driving towards the main physical space that the story will take place in. But the mood of this beginning is very much unlike Totoro’s.

In Totoro, the two main characters, Satsuki and Mei, feel like they’re on a big adventure. Even though they only have a general idea of where they’re going, they’re eating candy, curiously glancing out at their new environment, and getting into active play as soon as they arrive, while Jo Hisaishi’s music sets up a film of curiosity and childlike imagination.

In short, these kids can’t wait to get there.

Meanwhile, in her film’s introduction, Chihiro is just… meh.

We find Chihiro completely resigned to the situation she’s in. She’s already gone through the packet of off-brand Pocky, and the flowers she’s holding on to are almost wilted. And Hisaishi’s choice of music for this scene is not uplifting, but rather evokes a sense of melancholy.

While Chihiro does not look back from the beginning of the car ride that we see, she isn’t inclined to look forward either. She only gets up to look out from the car when specifically prompted to, with mixed results.

When we view the film through the lens of movement, this is our starting point. Chihiro starts out from a position of movement, but she is completely passive in that movement. She is not going, she is being taken.

Which brings us back to the base mythological story function that Joseph Campbell called the “psychological function”, and is more commonly referred to as liminal stories. These are the myths (and associated rites depending on the culture) that, writes Campbell, “carry the individual through the stages of his life”, and many times, they involve trials, initiations, and symbolic or literal death and rebirth.

In Spirited Away, the world of the bathhouse is a sort of otherworld or underworld and acts both as a liminal space for Chihiro – who is at the brink between childhood and adolescence – as well as a deterrent space for those who are not ready for transformation.

The world of the bathhouse is a place where humans aren’t supposed to be, but they can travel there, and they can use it as a place of transformation, but can also get stuck if they’re not careful.

Stuck in the underworld

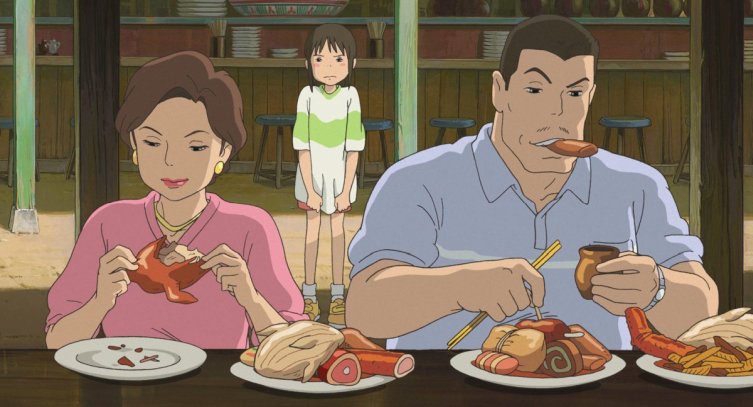

Now, “getting stuck in an underworld” is a sub-trope of its own, and Chihiro’s parents are a good example of people accidentally entering a non-human space unprepared and messing up bigtime.

The parents literally fail the very first test, “don’t gorge yourself on other people’s food without being invited to eat“, which arguably is a much easier test than “don’t look back towards the thing you have an emotional attachment to“.

Chihiro winds up in the place not out of her own wish, but does realise pretty quickly that while she doesn’t want to be in this inbetween space, she is already there and must adapt to survive.

The reason she is the hero of the story and a model for us to follow is that she does end up fully accepting the journey, learning how this special world works, and earning her way through and out of it.

The Bathhouse: Underworld or Otherworld?

A quick aside. I’ve been using underworld and otherworld interchangeably throughout this text, and that is for our reasons in this article we’re talking about any world that is non-human that humans can temporarily enter.

That said, the exact spatial relationship of different worlds is a super interesting question when you’re trying to figure out cosmologies or to get a sense of how a culture organises what relation things are to each other. So whether a place is specifically an underworld (literally below ours) or an otherworld (in a parallel space with ours) is again something that depends on the specific mythological worldbuilding.

This is one place where you can see Spirited Away using a mixture of mythologies.

Since Japanese culture is built on the ancient mythologies of Shinto, it does have some vertical spatiality. Yomi, the land of the dead is technically beneath the Earth, which we know from the time of the 8th Century Kojiki. There’s apparently a big boulder blocking one entrance in Izumo province, and there’s another place where the seas all enter the earth.

However, Shinto as a whole considers our world and the world of the kami as parallel. Since The Bathhouse is a place for all sorts of spirits to visit, it’s spacially on the same level as where Chihiro and her parents get out of the car. It is separated from human space by many things: the tunnel, the waiting room, the riverbed, the restaurant area, and the bridge.

While we do venture into “souls of what are possibly humans” territory in the train sequence, that is actually a very big drop below The Bathhouse, so overall I’m inclined to call the place Chihiro enters an otherworld rather than an underworld.

The Haku connection

Unlike her parents, Chihiro doesn’t fail the very first test and instinctively pushes forward and seeks out help, which is how Haku becomes her guide from the beginning.

The eventual proof of Chihiro’s adeptness in the otherworld comes in the third act of the film, when Haku gets gravely injured — at this point, Chihiro becomes Haku’s helper in the same way Haku became her’s in the beginning of the story.

This way, Chihiro returns the favour by helping out Haku who, we also learn, is yet another person who ventured into this liminal space and got stuck. Haku’s story is not the same as that of Chihiro’s parents, but with the same result: he’s unable to move on from until he gets help.

(A sidenote, but the help comes through eating, which is a recurring theme in the film that I mentioned in my introductory video.)

But at the end of the story, Haku is inherently a being whose home is the otherworld as much as Chihiro inherently belongs to the human world. This means that he’s also the person that she cannot take with her when she leaves.

Rules of underworld travel

On the surface, the core of underworld-visiting stories is always some sort of divine being setting the rule (Hades in the Greek story, Izanami in the Japanese story, God in the Old Testament story), and you gotta follow the rule because it’s a divine being setting the rule. So that’s part of it as well — can you follow divine instruction?

In Spirited Away, there’s no all-knowing divine entity who is the absolute ruler of that domain, knows everything and enforces the rules. (Again an element that strengthens the argument that Chihiro has ventured through to the general Shinto otherworld of the kamis, and is going from place to place within that space.)

But there is Haku, who has been her guide from the beginning, and is technically a river god. So at this last moment, he steps back into that role of advisor to say “Don’t look back”. It’s not his rule, it’s not anyone’s rule – it’s how this world works.

We could let this go here and say, well, Chihiro is told not to look back because that’s how it is in mythologies, and it’s a direct reference to that.

However, Miyazaki doesn’t do superficial references. He makes references only when they have something specific to say in the context of the story.

I think for Chihiro, the trial is being able to leave this place without the emotional attachment that would not let her move on in her life.

And in this scene, Haku becomes the personified symbol of the possibility of emotional attachment.

The question is, does Chihiro associate her journey’s goal with having reunited with Haku, or is she able to recognise that helping Haku restore his memory was one of the things she did as part of her quest but not a sign that she should form a permanent attachment, taking the spiritual learnings with her into her human life?

The entire story of Spirited Away is about Chihiro’s maturation and coming-of-age so Miyazaki calls back to these stories to show that Chihiro actually has learned all the things she needed to, and is ready to move on. And she does.

The symbolism of Chihiro’s hair band

There’s one last piece of the puzzle, and that’s delivered through an innocuous late-stage object in the film: Chihiro’s harid band.

It’s a general rule in mythologies that humans can’t stay indefinitely in otherworlds without consequences — unless they permanently want to leave their human existence. It’s a trope of its own that we can discuss at another time.

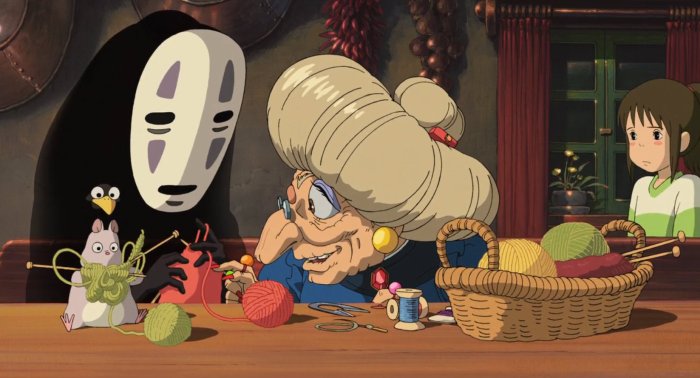

What Chihiro is able to take with her from her time in the otherworld is the experience and the knowledge of how to live well and the qualities of working together with friends. This is symbolised by the hair band that Boh, Kaonashi and Yubaba’s harpy servant weave for her in Zeniba’s cabin. The hair band perfectly encapsulates her learning and that notion is deeper than her actual physical connection to the space.

By now you know that Miyazaki never accidentally puts things in his films. So it might not be surprising at this point that a hair piece also features in the Izanagi-Izanami story, where Izanagi takes off and throws hiw hair band (then made of vines) to the ground because he leaves the underworld while having to escape from the fury of Izanami.

This element in the story gets its own reversal in Spirited Away: Izanagi loses a hair ornament, and Chihiro gains one. A seemingly tiny but significant change, to me this symbolises that while Izanagi needs to leave the underworld in a chaotic manner, failing his quest, lesson unlearned, Chihiro leaves her underworld in a peaceful manner, trials passed, lesson learned.

In fact, the art of silk braiding is an ancient Japanese art form called kumihimo. Making silk braids is not a ceremonial act itself, but braids have traditionally been connected with religious ceremonies through their use as ornaments in matsuri equipment, for tea ceremony containers, temple decorations and so on. In the Heian Period, it was actually Buddhist monks who would create most of the braiding. Makoto Shinkai’s Your Name greatly expands on the kumihimo concept and goes even deeper in the symbolism of weaving things together and how weaving can represent a form of connection between people and throughout time.

This way, the hair band comes to literally tie up everything we’ve talked about before. It represents the memories and the experience that she has gone through, but it is also reminder to us that the real value of a place is not staying in that place – and a value of a time spent with others is not in trying to extend that time indefinitely. When your time spent somewhere or with someone has come to its natural end, you can actively choose to let it go — and by doing so, you can move on without getting stuck.

How Chihiro passes her trial

So the very short answer to the question we embarked on in the very beginning, Chihiro doesn’t look back because she learned her lessons.

And we know she’s learned her lessons, because we get two shots of the hair band that she got.

The first time, she almost turns back but doesn’t.

The second time in the very last scene, she does look back at the tunnel, but she’s already out of the otherworld so she’s allowed to look back now and reflect on her journey: even though that world is no longer available for her, the real value — the teachings — she takes with herself.

This makes the end of Spirited Away remind me of a previous Miyazaki film, Castle in the Sky, which ends on a similar takeaway: the film’s central heroes are unable to stay in the mystical place they found, and they don’t take any treasures from it — the real value was in the spiritual experience they have lived through. (For a full discussion of the mythological and spiritual meaning of Castle in the Sky’s ending, check out the third episode of our Castle of the Sky analysis podcast.)

Now it’s your turn!

What did you think of this interpretation?

For simplicity’s sake (and because these are the three stories I’m most familiar with) I stuck to the three most well-known mythological origins of the “Don’t look back” trope. If I’ve left out one you’re familiar with, let me know in the comments!

If you’d like to have your question about a Miyazaki film be made into a Moon Rabbit article or video, leave a message on the Moon Rabbit Hotline!

And if you haven’t yet, be sure to grab a free copy of Studio Ghibli Secrets, my one-stop reference guide to Miyazaki storytelling!

Get the Studio Ghibli Secrets Guide!

Credits

Article by Adam Dobay, with additional research from Nora Selmeczi.

Spirited Away © 2001 Studio Ghibli – NDDTM/GKids.

My Neighbour Totoro © 1988 Studio Ghibli.

Savitri, Satyavan & Yama is by M. V. Dhurandhar, 1924.

Distracted boyfriend memes based on “Disloyal man walking with his girlfriend” © Antonio Guillem, 2015.

Liked this post? There’s more!

If you liked this post, check out:

- my ever-evolving list of recommended underworld-faring films & games (it was written on Halloween but works anytime).

- and if you haven’t yet, watch or read my introduction to the themes of Spirited Away, including growing up and the façade system inherent to Japanese society.

Hi Adam!

I’ll try to synthetize my thoughts because they tend to go all over place (it seems to happen a lot with ghibli, weird huh?).

So first of all, thank you for this really great article even thought there’s some misspellings (actually i love that because it demonstrates how passionate you are about spirited away( and ghibli in general).

Second, how did you know like, i literally rewatched spirited away YESTERDAY?! , plus it’s the first time i made the connection between the “don’t look back” with Orpheus and Eurydice so yeah i’m sarting to doubt this is a coincidence.

Allright, introduction done! Here’s what i really wanted to say.

You mentioned Haku helping and guiding Chihiro at the beginning and vice versa in the third act.

I want to talk about the very first right after Haku leaves Chihiro and she goes downstairs on the edge of the bathhouse to ask Kamaji for a job. She tries to go down step by step (even sitting) but one broke, she fall and she starts running down with a lot of momentum and crashes full force onto a wall. I noticed a parallel with the chase scene between Chihiro and Kaonashi after she try to help him and guide him outside the bathhouse (he ate the green thing Chihiro gave him, again eating is the solution). At the end of the stairs, she still hits the wall but she recovers way more quickly but not Kaonashi.

What i’m trying to say is that she also helped No-face much like she was helped by haku before. In these two scenes the “guided” is full of fear whereas the “guide” is sure of him/herself. Chihiro was lost, No face was lost but they were put back on the right track (respectively by Haku and Chihiro) so they can walk by themself and be active in their lives.

There’s so much more i could say about these two particular scenes but i’ll stop there cuz i don’t want to get off topic too much and it’s almost an article on it’s own already lol.

I hope that was not too messy and sorry if there’s any misspellings, blame my passion!

Ghiblitly yours,

Paul

PS: As i was writing this comment, i felt as if i was just starting to really understand Spirited Away. So much thing to discover, how exciting! Miyazaki’s works are always full of rabbit holes!

Love the in-depth analysis! I missed the references and allusions to other mythology at first but I think it makes perfect sense. Great work! Now I need to watch it again!

I love these film readings. My question is whether Haku has learned any lessons that would allow him to leave and not look back? He really has no where to go, he knows his name and is no longer Yubabas slave. How can he say he will meet Chihiro again if he is trapped in the other world?

Reincarnation maybe?

Thank you for sharing this! My question is how did Chihiro know which pigs were her parents? And if the pigs were indistinguishable, then how did Chihiro figure out that none of the pigs were her parents at the end?

Amazing analysis, I’m quite speechless.

The moment the movie took its turn the way it did and Chihiro’s journey began, I knew nothing was randomly said, done nor created. The symbolism of that wold and the metaphorical essence of each scene just- it blew me away, and that’s why I ventured on this post. Excellent.