How do you sum up Miyazaki’s work in a sentence?

Back in 2014, a cinema in my home town of Budapest, Hungary called me to ask if I could hold an introductory talk on Hayao Miyazaki before the premiere of his then-final work The Wind Rises – a film I worked with for 3 months, having been in charge of its official Hungarian translation.

So when I got the call my first thought was:

“Yes! Finally! I’ll tell them EVERYTHING I know about this guy and ALL his films from my last four years of research! It’ll be a six-hour talk! No, eighteen! No, forty-seven! With 2000 slides! Mwhahahaha!”

Then the lady on the other end of the line continued: “you’ll have half an hour before the film”.

Oh, I love limited timeframes. I really do.

When you have a limited time to talk about your favourite research subject, you have to really think: What’s the most important thing? What is the one thread that has to be in there?

I took a long look at Miyazaki’s life work

and found 3 recurring themes:

Wind.

Women.

& Revolution.

And for Miyazaki, the three are closely linked.

Hi, I’m Adam Dobay. I have a background in film theory focusing on mythology and gender roles in storytelling. I’ve also spent ten years in film production as writer, script doctor and translator before coming back to study stories to help people understand and tell better stories, whether they’re filmmakers, writers or people who want to immerse themselves deeper in the stories they resonate with.

I’ve held over 400 talks since 2010 on topics ranging from Japanese anime to Hollywood’s pop mythology. I also ran a two-semester undergraduate course, Therapy and Enlightenment in Anime for two years at the Dharma Gate Buddhist College.

Studio Ghibli Secrets – the one-page version

Here’s the story arc I believe is woven through Miyazaki’s life work:

- He dedicates his entire life to promoting peace and non-aggressive solutions. (Growing up during World War II, this is not a surprise.)

- In his view, what lead to Japan’s destruction in the war was a society based on hierarchy, aggression, the oppression of the weak by the strong, and overreliance on technology.

- Bad systems of society involve rigid class systems – in better systems, classes work together peacefully (if they exist at all).

- As a solution, he proposes empowering women. By empowering women, Miyazaki believes society will be more built on exemplary traits he associates with women like fairness or inclusion, but also wit, practicality, perseverance and hard work.

- Empowering women also leads to a reconnection with the natural world that is mystical, mythological, and altogether better than the current world that humanity has managed to build.

- It’s all about balance. Nature has balance, so should human society. This ties the concept of equality together – equality of genders and equality of classes.

- The best way to reach all generations with this message is through popular film.

- And finally, Miyazaki now believes that he failed.

On the last point, I disagree with him. I firmly believe Miyazaki reformed Japanese animation. He is one of the reasons that anime can be as serious as it can be, and that it can reach and affect huge audiences – way beyond Japan.

Miyazaki also gave a brand new vision for his country and changed millions of life through his art. But it also wouldn’t be Miyazaki if he didn’t think that all this didn’t amount to much in the end.

What you’ll learn in this guide

Most people who write about Miyazaki interpret him through a Western lens. But if you want to understand his stories fully, you have to take into account the unique context of his upbringing, his connection to Japanese culture and mythology, and how he reacts to the society around him.

This is exactly what I’ve been focusing on in my research of the past few years: on how we, with sometimes very different cultural backgrounds, can understand what Miyazaki says half a world away.

By giving pointers to many Ghibli films below with this approach in mind, I‘m sure you’ll find new ways to see these films even if you’ve watched them all a million times. But you also don’t need to be a “superfan”: you won’t be lost even if you haven’t seen most or any of his films.

Finally, while I mainly focus on Miyazaki, I’ll be throwing in an occasional film from Studio Ghibli’s second most important director, Isao Takahata.

Here are the main things you’ll learn from this guide

You can also use this as a table of contents, and click through the topic that catches your eyes first!

- Why the sheer amount of movies Miyazaki has made is incredible

- Personal mythology in Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind

- The innovations of Laputa, Castle in the Sky

- Why Miyazaki heroes run all the time

- How Japan’s culture connects nature with childhood and divinity

- The two places Studio Ghibli got its name from

- How Miyazaki’s views on women clashes with Japanese’s society

- How Totoro empowers through the mythology of wind

- The social parallels of Kiki’s Delivery Service

- What Porco Rosso has to do with The Wind Rises

- Isao Takahata, Pom Poko and the theme of “we’ve lost something”

- Princess Mononoke and the mediaeval paradigm shift

- How Spirited Away is an initiation film for a generation

- Why Howl’s Moving Castle is a symbol of modern Japan

- Why Ponyo is the film of personal hope

- How Miyazaki’s childhood affects the story of The Wind Rises

- Why The Wind Rises is a prompt to face history and the present

Introduction: Why Miyazaki is factually amazing

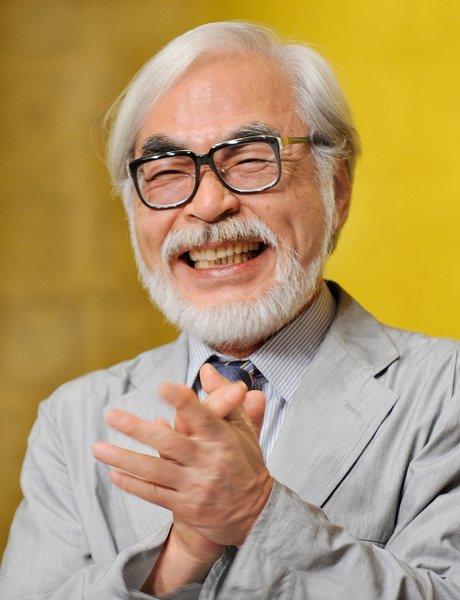

If for some reason you’ve never seen an image of Hayao Miyazaki, this is approximately what he looks like.

In most publications, they usually use a photo of him where he’s quite morose. Now this shot was taken after his resignation… when he realized he won’t have any more deadlines.

But here’s a perhaps more telling rendition by artist Ryan Smallman (who I’m very grateful to for letting me use his artwork):

You can be sure to find your favourites on this. We have a highly prolific filmmaker in Miyazaki, especially considering the scope of animated films. When doing live action, you might be able to produce a short film in a matter of months. In animation, that’s a year at least. And what would take 2-3 years in live action, it will take five or six in animation. Which makes Miyazaki especially prolific.

He’s been in the industry since the seventies, and just recently put down the pencil. Or so they say. He loves it too much to retire. We’ll see at the next premiere 3 years from now where I’ll again talk about how he’s just resigned.[1]

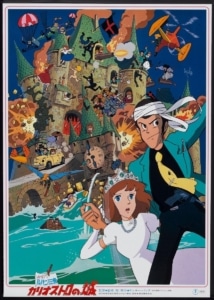

Not everyone is familiar with Miyazaki’s very first directing venture, Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro. (Though considering his worldwide appeal, that’s still a lot of people.)

This was the very first film Miyazaki directed, back in 1979. And you can already see the kind of “adventure with lots of chases” format in it that will return in his other early films like Laputa – Castle in the Sky and Porco Rosso.

While the Lupin III brand itself was not created by Miyazaki, he had been working at the Toei company long enough to get him his first shot at directing. But by that time, he was already notorious for poking his nose into everything. One thing he did repeatedly was tell people to rewrite scripts of the films he was working on because he didn’t like the story. Just imagine, a rookie colleague, fresh in the job, walks up to you, the established director, to rewrite your film because he doesn’t like it.

A very unusual and risky thing to pull in any company, let alone in Japan’s strict workplace hierarchy. So the most surprising thing is that this approach actually worked!

“Here’s a new ending for Gulliver, I don’t like the old one” – Miyazaki said to the director on one of his first projects. And he got the changes through, whatever they were. The guy definitely had charisma already in the 60s.

Part 1: High adventure meets deep mythology

By the time Lupin comes along, you can already see some of the elements that will be prominent in the first era of Miyazaki films. Adventurous young people, slapstick characters doing slapstick comedy, and a good number of scenes taking place in or around specific vehicles.

A final significant element of this period is that during the making of Lupin III, Miyazaki really hit it off with Isao Takahata, who would become a lifelong friend and would also direct films after Studio Ghibli is formed.

Personal mythology in Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind

And with that, we get to the eighties.

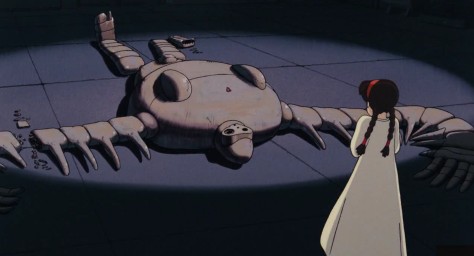

1984 was the year of the big team-up. There was Miyazaki, there was Takahata, and since Miyazaki couldn’t draw huge, menacing robots, he asked a young colleague called Hideaki Anno, who would go on to make another little known robot anime that you might have heard of.

Miyazaki basically went, “I can’t animate this huge atomic god beast, would you?” And Anno did take over and do this one character in the film that is the Resurrected God Warrior.

So this is ’84, and while the group is not yet formally known as Studio Ghibli, the team is already assembled. This was the first project of the group that Miyazaki liked to work with. And already as early as Nausicaä we find some of Miyazaki’s strongest motifs. Most of the themes that Miyazaki cares deeply about are already in there, and it’s no coincidence. He adapts Nausicaä from his own manga – and not even the whole thing, just the first two books of what would become a huge, six-volume work. Despite that, the film stands on its own.

Basically, everything that can provide a source of conflict in a Miyazaki film can be found in Nausicaä.

#1: man and nature… would not be in conflict if man wasn’t an idiot.

#2: man and machine… would not be in conflict, and so on, you get it.

And why these topics keeps coming back is very clear if you know a bit about Shinto. Now Shinto is often referred to as Japan’s aboriginal religion, or “nature religion”. That’s sorta-kinda okay for simplicity’s sake, but since you’re already reading this, I believe you can process the fact that while Shinto does have its fair share of deep spiritual elements, it’s not a religion in any Western sense of the word. I like to go with the more complex definition that Shinto is more of a cultural amalgamation of various local folk story and belief systems.

So when it comes to Miyazaki, he’s not a religious person – again, in the Western sense. In Japan you don’t believe that these beings are there. They’re just there. That’s one big conceptual difference between Western and Eastern spiritual thinking.

Anyone who saw half of a Miyazaki film will realize just how much he likes to play with the elements, putting one element in conflict with another one and seeing what happens. He also connecting elements with attributes. In a Miyazaki-film, wind is always something that can subvert and change, but overall it’s also a pleasant sort of thing.

And especially in his early films, Miyazaki likes to put wind in contrast with fire, which is always something that destroys and devastates.

When fire comes, you usually don’t like it, and you can’t control it, but it comes anyway. This is very basic in Eastern thinking overall, by the way: things happen. Life is something that happens to you, and your choice lies only in how you react to the things that happen to you.

Also, if you’re Japanese, you’re born into the country with the most earthquakes per capita. And over the millennia, this creates a culture that is centred on being in the present moment. We are in the now. We have to be in the now, as who knows, there may be an earthquake tomorrow – like there was one just a few years ago – and then everything falls apart, and we have to start over from the beginning.

This is a recurring theme not just with Miyazaki, but in a lot of anime where we have nice big apocalypses. In Japan, you don’t just call Bruce Willis in to prevent your apocalypse like you do in Hollywood.

The apocalypse happens. We can’t avoid it, but we can survive it. And the films about the apocalypse are not about how to prevent the apocalypse, but how to survive it, and then what to do with yourself afterwards.

The innovations of Laputa, Castle in the Sky

Now Laputa – Castle in the Sky is a tad more lighthearted. The only reason it has Castle in the Sky as part of the title in many countries is that you can’t distribute a film called “La puta” in any country with a Spanish speaking audience. That’s why the US title became Castle in the Sky, which was used in other countries as a sub-title. A similar thing happened when the US distributor retitled Nausicaä into Warriors of the Wind, which became, the title of film in Hungarian title, among others. The wind has no warriors in the film, but who cares? Local distributors and their film titling happens on a very distant planet.

Miyazaki, in his college days, was a member of a children’s book or fairy tale club – there weren’t really university manga clubs back in the sixties, so he went with children’s literature. So he spent a lot of time with how fairy tales are constructed, with how you tell a story, what Western folklore is like, what Eastern folklore is like, and then these become the building blocks of his stories.

And in Laputa, too, you have this distant mythological image of a place that existed in the past – in this case, the floating island – that we once lost. And he continues the mythology with what happens if we were to find this place again, and how it falls apart, and how we then have to go and live on. And again, we reach this place with our flying machines.

Why Miyazaki heroes run all the time

And again, it’s enough to see half a Miyazaki film to know how his heroes run, boy can they run. “Why do these people run so fast?” Miyazaki was once asked I think regarding Princess Mononoke, whose heroes run a lot and all the time. And Miyazaki said, “This is the dynamism of youth.”

That’s why he likes young heroes, and that is why in Laputa we have protagonists even younger than we had in Nausicaä. Because they just go and do things. They don’t just sit around theorizing. Sometimes they do sit and philosophize, like Eastern heroes generally do, but they mostly run and do what they think is right, with great conviction, and it then turns out they were right.

And it’s also why most of these heroes are women. A fellow lecturer of mine, Akemi Solloway Tanaka, who actually comes from an old samurai family, and currently works as a Japanese cultural consultant in London, told me how flabbergasted everyone was when Nausicaä came out in Japan – you just didn’t have that kind of film in Japan before that.

And the reason for that is that it was a fantasy world, but not just in the sense of the film’s genre. It is also a social fantasy where a woman, an individual, comes and her actions change the entire society.

I’m sure you know that Japan, similarly to other Eastern cultures, is a collectivistic society. Everything is built around groups. My work group, my family group, and so on – and if I happen to be a man, the work group trumps everything.

And society is about how I can serve each group. When someone rises out of a collective, it’s normally considered rare, odd, possibly controversial. And Miyazaki brings in this Western kind of individual hero with heroic acts that they decide for themselves. But at the same they also serve a collective, which is ultimately beyond the collective of any single human group: the collective of nature.

How Japan’s culture connects nature with childhood and divinity

Japan thinks of nature in exactly the opposite way that we do. In the West we have the dominant concept of an original sin separating divinity from humanity and humanity from nature. Japan has the concept of an original purity where humanity can experience divinity through nature.

In Shinto thinking, whatever nature brings cannot be wrong. And that includes earthquakes, illness and death. It’s all natural. Both life and death are natural. It is us who do stupid things. We humans, and we adults mess thing up. Which is why the Japanese also love childhood. Children retain their innate connection to the divinity of nature, and by reconnecting with our childlikeness, we too can reconnect with divinity.

The two places Studio Ghibli got its name from

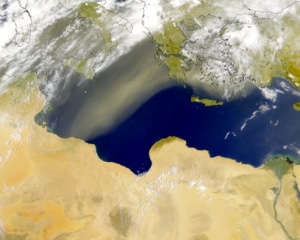

To produce Laputa, Studio Ghibli is created. And the name Ghibli comes from two different but connected sources. On the image above is the “Ghibli”, a Caproni-309 type Italian aircraft. If the name Caproni is familiar, he is an Italian engineer and aircraft designer who appears as the main character’s mentor in The Wind Rises. And the code name of the aircraft above was Ghibli. But it’s not the plane that they named the studio after.

Ghibli is a word in Arabic originating in Lybia. It is “ghib-lee” when you pronounce it in Italian, and “ji-bu-ree” if you pronounce it in Japanese – making both pronunciations technically correct. Whichever way you say it, Ghibli refers to the sirocco wind that comes in from Lybia, sprinkling dewy sand across the Mediterranean. Quite a pleasant phenomenon.

And even this is not the exact reason that the studio is called Ghibli. They simply named the studio after a type of wind because they wanted to bring new winds into Japanese animation.

So in the end, Studio Ghibli is named after the principle that Miyazaki wants to see in his films, and in society as achieved through his films.

How Miyazaki’s views on women clashes with Japanese society

One thing Miyazaki noticed is that women in Japanese society are in quite a bad position. From an early age he saw his mother, a well-read, intelligent and eloquent woman who always spoke her mind (remind you of any characters?). He probably also saw how Japanese mythology is full of female figures in prominent roles, and how the importance attributed to goddesses does not carry over to society.

Japan is late to the equality game: with its family-centric Confucian background where women are subservient to men in every way, women were granted most basic rights only after World War II (like elsewhere, a radical shift on gender roles). Society is not quick to adapt: Still today, Japanese woman are expected to be housewives and mothers above all else, and society is practically structured in a way that once you leave work to start a family, there is no way back. Change is slow.[2]

This is one reason Miyazaki makes most of his protagonists female, and many have followed in his footsteps since. I’m quite convinced that the ground-breaking character of Nausicaä laid the groundwork for the renaissance of the magical girl character of the 1990’s with Sailor Moon, leading to a decade of “girl power” in popular culture with lasting effects.

Miyazaki’s films are also followed by an upsurge in innovative female heroes, as well as male heroes who can’t take two steps on their own without female characters, female influence, or their mothers. And “mother” can mean the Mother archetype, so Mother Goddesses may also come into play.

How Totoro empowers through the mythology of wind

And at the pinnacle of Miyazaki’s early “mythological adventure” phase, we have My Neighbour Totoro. This is the original poster for the film, when they still thought one girl would be enough to tell the story. They later realized they need two, so the final version has two. But they kept the poster anyway.

Out of all Miyazaki films, Totoro has the most pronounced wind metaphor.

There’s one sequence in the middle of the film that you might remember, in the scene where they jump on that makeshift whirly flying thing.

And as the two girls and Totoro sail through the night sky, Dad looks out the window and notices there’s a bit of a breeze tonight. He has absolutely no clue about the cosmic event outside the window.

And in the same sequence, the older sister remarks, “We are the wind!”

This is one of the most mythological sentences uttered in a Miyazaki movie – a spiritual interpretation of what wind is. We ourselves are the force that can manifest in this way in the world. This is what these girls learn from this large, furry Shinto spirit. And that’s the lesson for us, too.

Part 2: Reality seeps in

The social parallels of Kiki’s Delivery Service

I tried to find the posters that show people flying. Let’s just say it wasn’t hard.

I won’t go into Kiki’s Delivery Service too much here, but basically we have a light-hearted version of the concepts Miyazaki introduced in previous films.

Kiki, depending on how you look at it, is either about how to be a female entrepreneur in Japan, or just how to grow up as a female person in today’s Japan. It’s saying “I’ll go and figure out what I want to do with my life.”

There’s a bit of adolescent anxiety thrown in, like Spirited Away will later, but just a bit. In Kiki, exploring the world is fun, it’s an adventure. How will I fit in? How will I serve Japanese society? And how will I remain myself? Those are the questions it seeks answers to.

What Porco Rosso has to do with The Wind Rises

Let’s move on to Porco Rosso. What’s interesting there is that it was originally supposed to be a 30-minute short.

“Let’s have a funny pig flying around and show it as an in-flight film for ultra-tired Japanese business-men who are coming home from business meetings in Hong Kong.”

That is the concept they started with, but they ended up with a full 90-minute film. They just loved it too much at the studio. And it was just too close to Miyazaki’s heart.

Porco Rosso is where the world war theme first appears rather directly, but is still distant – the story remains light-hearted throughout so there’s only the occasional jab here and there.

Still, there is a faint undertone of loss and sadness in Porco Rosso, and in Porco’s character we can see the regret and also the acknowledgement of the breaking down of an old world order that was shown to only bring destruction – as is shown in that haunting dream sequence.

So Porco, the rare male Miyazaki hero, wanders, having become disgusted by that system that is based on the battles of male warriors over who dominates over the other. And, by extension, he is disgusted by himself – hence the pig form. And he stays a pig until he can find the positive aspects of his maleness, and values that are worth fighting for.

A lot of people still tie The Wind Rises directly to Porco Rosso – like The Wind Rises is some sort of a sequel –, which anyone who has seen both movies can immediately tell is not true. The confusion over this comes from the fact that Miyazaki did talk about plans to do a Porco Rosso 2, and that when he drew a prequel/prototype manga for The Wind Rises (also about the life of Jiro Horikoshi and setting up the basic structure for the film), he drew Jiro as a pig.

So that pig motif is definitely in there, then again, Miyazaki draws himself as a pig, so when he does a sketch of people from the studio, you know which one Miyazaki is because he’s the pig.

(Unless Miyazaki draws everyone in the company as pigs, but you can somehow still tell which is meant to represent him.)

Isao Takahata, Pom Poko and the theme of “we’ve lost something”

As a bit of a contrast, here’s a film from the same period that Miyazaki’s friend and colleague Isao Takahata makes: Pom Poko, or for the full title, Heisei-era Tanuki War Ponpoko.

I think it would have actually benefited Western audiences if at least “war” was kept in translation. I know too many people who sat down to watch this film and went:

“Oh, look at all the cute animals!

…that are now all dead.”

Pom Poko is not a happy family movie. And the reason for that is that Takahata’s main recurring motif as a director is the expression of “we’ve lost something”. And perhaps this film is the best expression of the confusion, the anger, the sadness, and the eventual reluctant acceptance of this loss.

Many artists share Takahata’s feelings regarding Japan’s period of rapid after-war modernization from the 1950’s onwards. It’s in Miyazaki’s works as well, but he always tries to focus on moving on in an optimistic way after the loss, while Takahata focuses on that loss in hopes of understanding it and communicating that understanding.

There’s really no wonder why for the film’s protagonists, Takahata chooses the tanuki – the playful shapeshifting creatures associated with play and booze, with luck and light-headedness, with prosperity and, also, sex (a.k.a. prosperity in reproduction). The tanukis’ connection to nature and their childlike quality makes them the ideal personification for the natural world. As Takahata argues through the film, Japan’s connection to nature is run over by the sheer speed of modernization. Or, for an even radical interpretation you could even say that the sheer fact of modernization is enough to lose this connection.

“Was it worth it?” is one of the big questions of not only this film, but many other works of animation made by the people who lived through these changes. This fracture, this trauma is very strong and frequently returns in more serious works of anime. The great contradiction is this: We live in this great, technologically modern society, but we’ve left something behind that would have been very important to keep. And what we’ve left behind is the world of our past.

Having to let go of that past is a source of great sorrow. At the same time, getting here means we’ve survived. A lot of the time, the conclusion of a film depends on where they choose to stand on this scale, on what they think is stronger: the sadness of loss, or the hope for a better future.

Princess Mononoke and the mediaeval paradigm shift

And with that thought we get to Princess Mononoke, the poster for which is a better indicator in deciding whether to take your 4 year-old than Pom Poko’s was.

There’s so many layers of this film that I’m preparing separate material for it for the blog as we speak.

For now, within the confines of this book and its main themes, I’d mainly like to mention a number of basic points to start out with.

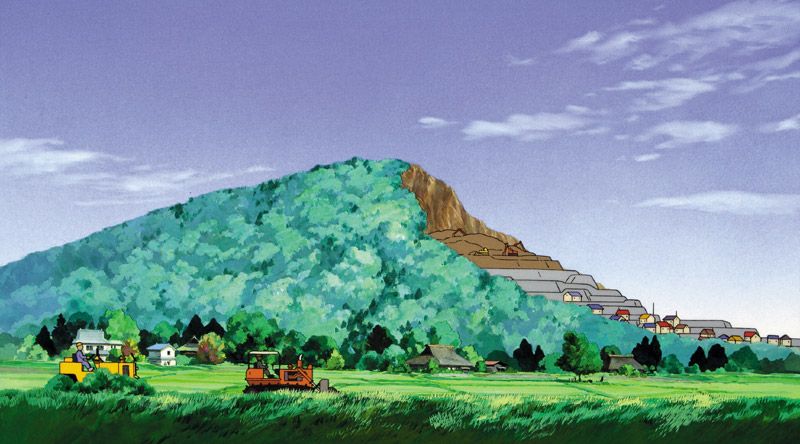

You can almost always draw parallels between the work of Miyazaki and Takahata, and it’s an interesting exercise to do that with Pom Poko and Mononoke. Both are set at historical turning points, both stories take place in a time of chaotic change, and both are set in mythologized versions of one specific era of Japanese history.

Even the question is the same: “Where did we go wrong?” And for Mononoke, the answer is right there in the beginning. Think about it: what is the inciting incident for the film? What has turned the boar god into a demon?

Human technology used as a weapon.

Here’s Miyazaki’s ambivalence to technology expressed in a poetic way. Technology is the way to progress, and it is also the way of destruction. Technology is the fire to the quiet wind of the forest. It is bulky and it is arrogant, not unlike the humans using technology to assert dominance over nature, forgetting where we came from.

For Miyazaki in Princess Mononoke, the price of rapid progress is the act of killing off our gods, and losing our connection to these wild, ancestral, totemic animal powers – again, raising the question: was it worth it?

How Spirited Away is an initiation film for a generation

The examination of this question continues in Spirited Away, where Chihiro’s highly capitalist parents think they can buy food from the gods on credit, and they promptly turn into pigs. If anyone asks me about Miyazaki’s views on bubble economy capitalism, I point to the first act of this film.

There’s a lot of commentary in this film that is about Japan’s economic policy in the 90’s, and healthy and unhealthy attitudes towards money that seems to have gone over the head of most people outside Japan.

While the film is chock full of Japanese references, and a lot of concepts, again, come from Shinto folklore, the generational coming-of-age story at the core seems to have been universal enough to not only be recognized in the West, but got Miyazaki an Oscar.

If you think about it, “My parents are pigs and I can do nothing about it” is actually a great summary of how anyone growing up in today’s world feels. Spirited Away is a story of a generation left alone, where the parent generation has become so disconnected that there is no teaching to be handed down to those growing up.

As a consequence, this is the generation that has to figure out everything on their own. Not because they’ve been sent on an adventure like in Kiki. For this generation there is no choice. “My parents don’t understand the world that I am finding myself in” is the experience the story comes from.

This fracture is the dilemma of modern Japan (and of modern anywhere). The changes have been so fast, that we have to figure out everything for ourselves, before we’re ready, or we’ll die trying. And it’s on us. Miyazaki can’t help. But he can give working models to use as templates.

Why Howl’s Moving Castle is a symbol of modern Japan

A good point of comparison to Chihiro is the low-key The Cat Returns – what happens on the outside in Chihiro all happens on the inside, no wonder it’s a story abundant with even more Jungian archetypes than usual.

The Cat Returns reframes Spirited Away’s the coming-of-age question to “How do I come to terms with the various parts of my soul or myself, all represented by cats?” For a challenge, give it a watch and look at what part of the protagonist’s identity each cat represents.

And rounding off the second phase of Miyazaki’s storytelling is Howl’s Moving Castle – another masterpiece that I am working on longer materials for. For now, let’s just say that it’s no coincidence that it’s not the protagonists who are on the poster. Put another way, what is on the poster is the protagonist, as in Howl, the moving castle is Japan itself.

In the design there’s a bit of old Japanese architecture, some monstery parts and some steampunk stuff to begin with. But the main point is the house always changes based on who’s living in it. By the end of the film we have a wizard, an apprentice, a girl with low self-esteem, a divine being and magic Grandma who was suddenly made redundant.

This is more common in the later Miyazaki films, piling up characters all fairy tale-like as the story goes along, representing different social classes, different ages, different walks of life, and somehow we all have to live together. And how do we all live together is the big question of contemporary Japan, and by extension, of our entire modern world.

Part 3: Accepting what cannot be changed

There’s a gradual tone shift in Miyazaki’s films as time goes on. In the early films, with Nausicaä, Laputa, and Totoro, there is genuine optimism for the world at large. There is a general tone of hope, and youth can change the world in a meaningful way. As films like Mononoke, Spirited Away and Howl come along, the protagonists more and more mainly react to changes in the world and having varying degrees of effect on it. And as we get to Miyazaki’s final films, characters seem to be placed to situations they absolutely cannot change, and they have to make the most of what they have, finding only personal meaning in their stories.

In this final part, I’d like to focus on just three films – if I leave a film out that happens to be your favourite, feel free to drop me a line and I’m happy to divulge into where I think that fits in the big picture.

Why Ponyo is the film of personal hope

So here’s Ponyo, a ridiculously cute adaptation of Wagner’s Ride of the Valkyries – you know, in the scene where this… thing runs on endless waves while turning into a human. Some people call her a mermaid, but that would be a bit of a stretch. Although in Italy they call Ponyo a siren, which is even weirder.

So by the time we get to Ponyo, we have a film of resignation. With protagonists around five years of age, we know they are not going to redeem the world. They redeem each other, which this film says is enough.

Meanwhile we see the bottom of the Japanese sea, full of litter. And there’s absolutely nothing anyone can do about it now.

What in Nausicaä was the total rejuvenation of the world and restoring the world to its balance, that’s nowhere to be found here. There’s a resignation, an acceptance that we’ve messed this up. Nothing we can do, we have to think of something new.

That is what’s going on in Ponyo. We have to return to that noble state of a child so little – in Japan, being three years old is a noble state of mind – in order to look at the world and figure something out. The adults in this film are the generation who grew up on the kinds of films that Nausicaä was. They didn’t save the world. Was it saveable? 1980’s Miyazaki sure thought it was.

Arrietty is the other film of acquiescence. While not Miyazaki’s direction, it’s his script, it’s his version of the story.

Again, the protagonists live in worlds that are not compatible with each other. Not even in size. One of them is a human, and the other is this small… something. And by the end – spoiler alert – they have to part ways. This is The Borrowers turned into a sad love story.

And to be honest, there aren’t that many meaningful similarities to the source material, especially when you look at the tone. There is this great sadness in Arrietty: we’d get along great, but we have to say goodbye because we are just not compatible. And even more importantly – we are not compatible by fate.

And while Ponyo is a jolly, playful sort of film, already on its deeper levels we find the melancholy of resignation. Which gets even stronger in Arrietty, and sets the tone for the film that’s Miyazaki’s swan song.

How Miyazaki’s childhood affects the story of The Wind Rises

The Wind Rises is not a happy film. (And that’s an understatement.)

We’ve seen it about 30 times with my co-translator, Edina Csalló, during our work of creating the Hungarian subtitles – so by now we kind of know it by heart. And what we found is that to really understand this very personal film, you have to look into Miyazaki’s own life, as the film’s story connects to his own life story on many points.

The tuberculosis plotline that we’ve seen appear before in Totoro, where it was the mother’s illness, is a childhood memory of Miyazaki’s, as his own mother was in a TB sanatorium for seven years. The same TB returns in this film. The plot takes place during Japan’s TB outbreak, so this is his mother’s story appearing here for a second time.

The other story is his dad’s story. Until I went back to look up what I forgot from Miyazaki’s early life after seeing this film, I hadn’t actually noticed that the factory that Miyazaki’s father led during the war – and where Miyazaki spent most of his childhood – happened to manufacture parts for the very same Zero airplanes that Jiro Horikoshi had created.

And the reason why Miyazaki had practically lived there was that the family had to leave their home in Tokyo in order to avoid being bombed. And the plane factory work floor over in Kanuma is where Miyazaki started drawing the aeroplanes he saw, made by his father who ran the factory, and his uncle who owned the factory outright.

So from his childhood, the path of Miyazaki’s father became intertwined with the concept of flight. And his progressive views, leaning into feminism, became connected to her mother. His mother was not your average Japanese housewife. She was smart and independent, had no problem talking back to her husband, and she had great intellectual conversations with her son.

Which led to a balanced relationship for Miyazaki to experience with his mum and dad. Both of them have some influence on this film, which is the most biographical that he’s made.

If you’ve seen a lot of Miyazaki films, you’ll notice a lot of parallels. And that’s perfectly deliberate, from the landscapes that he shows, to the words that people say, his old films keep coming back in references.

Why The Wind Rises is a prompt to face history and the present

And there’s another thing that I’ll leave up to you. And that is whether Miyazaki wants to confront you with his old films, or whether he himself wants to see if what he has made has turned out the way he wanted it to.

This is a film that raises questions. Miyazaki retires just as the government of Japan is, again, saying things like:

“Well, we might as well just take this no-war thing out of the constitution.” and “Well, we might as well just have a proper army again.“

And by ending his career with this very film, what Miyazaki is essentially saying is: “Look, I’ve been telling you what to do for 30 years. You didn’t get it. Here’s the realistic version.” He attributes his self-proclaimed “failure” to not getting his point across, but I don’t think it’s him who wasn’t clear enough.

In some ways Miyazaki is very strong about the wording of some of the dialogue, essentially telling people: “Wake up and realize the message before we end up how we ended up last time!”

It’s a historical path-finding quest. It brings the “Where have we gone wrong” question back, and I guess it’s not a big spoiler to tell you that Japan loses World War II in the film.

The Wind Rises is not an attempt to revise the past or to make it look better. It’s a serious confrontation both on a historical and a personal level.

The historical question is: What have we done, as a nation? What should we not forget about the actions leading to where arrived? What did we believe of ourselves that lead to these actions?

And then the personal question: What is the worth of what I have done? What is my creation used for?

And the third interpretation I suggest you to consider is the parallels between designing an airplane and designing an animated film. Very interesting to watch the film through that lens. There’s the one who draws and there’s the producer. And you have the one who draws the plane and you have the one who orders the plane – which is almost always the army, unfortunately.

There are so many of these nuances in there. At the same time, you have the usual: these vast Miyazaki-type landscapes, and the haunting music of Joe Hisaishi, who is Miyazaki’s perpetual composer. Which makes this a real sweeping epic of a swan song for Miyazaki, combining basically all of his life and his work as an animator.

One more thing for those who like this sort of trivia: the same Hideaki Anno who created and directed Evangelion, and who drew the God Warrior in Nausicaä, voices the main character in this film. He was around 53 when he did the film, and he’s absolutely perfect in delivering the voice for this twenty-something.

And one final final thing: I wanted to show you the film’s three original posters, they’re so cute.

A popular way to portray a kiss in Japan. They don’t want to embarrass you by showing something very direct so this is a quite Japanese way of showing a kiss: You see a person’s back, and there’s a face behind him, so those two are probably kissing! Ha! Subtle!

Now it’s your turn!

Thanks for sticking with this short book through to the end!

It was really fun and challenging to condense four years of research into one text, and I really appreciate you taking the time to read it all the way through.

Now I’d love to ask you to do two simple things:

- Please take a minute and think of a friend who you know would benefit from reading this book, and send them the link to this e-book: https://followthemoonrabbit.com/studio-ghibli-secrets/

You’ll help them out, and you’ll help me out! 🙂

- Please send me an e-mail to adam@followthemoonrabbit.com (just click on this link and you’ll get to your e-mail software – magic!) and let me know: what was the biggest insight you got from this book? What else would you be interested in reading about? By letting me know, you will help me develop more resources like this.

Finally, if you enjoyed this e-book, be sure to hop up to the Studio Ghibli section of my blog for more in-depth analyses on the films of Miyazaki, Takahata and more.

Talk to you soon!

Adam

[1] Note: Miyazaki proved me right. Since I first talked about this, he has indeed returned from retirement. At the time of this writing, he is back at the helm working on a short film called Boro the Caterpillar, and he has plans for a new feature for which his producer Toshio Suzuki is frantically trying to get funded.

[2] For more on this, Chris Kincaid has a good rundown on changing gender roles in Modern Japan on his blog: http://www.japanpowered.com/japan-culture/gender-roles-women-modern-japan