By the time they started making Princess Mononoke, Studio Ghibli was a big name – but their reputation was based on the cute fuzzy Totoro toys they were selling.

Hayao Miyazaki, being quite irritated at the simplification of his work, set out to make a film to revisit themes from My Neighbour Totoro but through a more mature lens, and to put audience misinterpretations to rest.

No, nature is not cute and fuzzy.

No, nature is not fragile and in need of your pity.

And no, humans don’t know better. We can be great, but we tend to be stupid, and we tend to mess up. Big time.

In this video:

- I take a look at how Miyazaki teaches us a lesson on the complexity of choices in a world of limited resources.

- I show how he incorporates elements of Shinto folklore, mediaeval Japanese history and contemporary attitudes towards nature to set up complex characters who need to face difficult decisions beyond the simplistic morality of ‘good’ or ‘bad’.

- And I reveal how he uses all these elements of the film to challenge his audience’s assumptions of the topics that Studio Ghibli keeps returning to.

(And there’s also a bit about how the English title is completely misleading.)

Watch the full video above, read the full transcript below, and don’t forget to grab your copy of the Studio Ghibli Secrets guide where I reveal the story patterns behind the multitude of Studio Ghibli films.

Get the Studio Ghibli Secrets Guide!

The many layers of Princess Mononoke – full text

- The making of Princess Mononoke

- The Shinto elements behind Princess Mononoke

- Princess Mononoke as a mature Totoro

- Princess Mononoke’s characters

- The role of Ashitaka

- The historical setting of Princess Mononoke

- Characters and motivations

- The role of the tree spirits (aka. the kodama)

- The Forest Spirit (aka. the Shishigami)

- Who is Princess Mononoke?

- The significance of Princess Mononoke’s mask

- The meaning of ‘mononoke’

- The real question of Princess Mononoke

Hello everyone and welcome to the second evening of our Summer of Ghibli original language specials here at the Duke of York’s. In today’s introduction to this film I want to briefly cover why Princess Mononoke was made, what makes it relevant to us here today, and why the English title is totally misleading in terms of understanding the film.

I’m Adam Dobay and I’m your host for this series. I have a background in film theory, storytelling and translation, one of my past projects being localizing Miyazaki’s to-date last film The Wind Rises. So I’m quite involved with Studio Ghibli, plus I personally think that Japanese mythology is one of the most interesting folklore systems to exist.

As with other Miyazaki films, a lot of deep mythology is in this film and knowing just a bit about it helps give a new layer of understanding, so I collected some of these elements for this introduction.

The making of Princess Mononoke

So by the time they start making this film, Studio Ghibli is already a big name, very well known, and already has a reputation. Problem is, the reputation is that they make cute and fuzzy things for children.

The Totoro character was such a hit that it kind of overpowered everything else the Studio had produced, and so while people got that there is an environmental message, the message was understood to be: „be nice to nature and take care of it because nature is gentle and vulnerable and needs our protection.”

Now the problem with that is that if you also look at Miyazaki’s earlier films like Nausicaa or Castle in the Sky, what you see is a complex examination of humanity’s relationship to nature where the problem is that we think we know better and that leads to us exploiting nature and using its resources to be destructive to ourselves or the environment.

And in this context, Totoro is an example where the children’s existence is so pure and innocent that it becomes very easy for them to live in harmony with the forces of nature around them. And the technology used in that film is minimal and only used for support.

The Shinto elements behind Princess Mononoke

Of course this is not something that Miyazaki came up with, it comes from Japan’s base culture, Shinto, which is often said to be a religion, but it’s not a religion in any Western sense of the word. Shinto is more accurately described as Japan’s native folk belief system which is made up of thousands and thousands of loosely connected local mythologies with some common base elements.

In Shinto, nature doesn’t exist for humanity to conquer, nature is where we come out of. Nature seen and unseen is the universal sacred ground of existence. And this means that the right way of life is in accordance with how nature works. This is the harmony principle, or wa.

Nature is sacred, every being and thing in nature is sacred, and so humans must strive to be in harmony with nature.

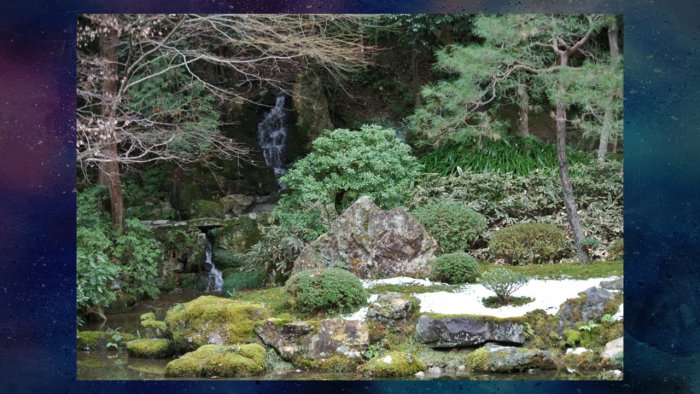

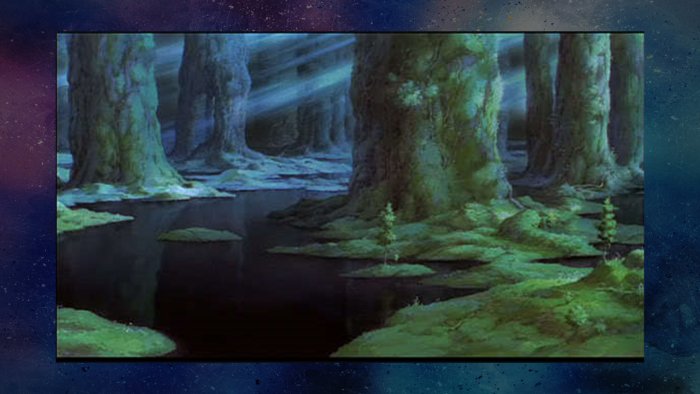

By the way, the photos are from Yakushima forest, the forest which the film is based on. And since the film there have been people who have been going there not as a fan thing, but as spiritual pilgrimage.

So when Buddhism comes into Japan later, it works well together with the Shinto ideas that are already there, and they coexist peacefully. This is a zen garden, which is a Buddhist idea built upon Shinto principles. I create and tend something harmonious and beautiful and that is the base of my meditation.

And in this combination system, everything that is corrupt is corrupt because it was corrupted by humans. Technology isn’t bad on it’s own, but we can use technology in a way that only benefits ourselves and is destructive for others.

And that is why as we get to Princess Mononoke, the film’s curse is a human curse, and it comes from gods being attacked with technology that was created with the intent to destroy. Destructive technology is not in line with the principles of Shinto.

Princess Mononoke as a mature Totoro

Of all of Miyazaki’s films, perhaps this is the one that most directly asks the question: “What decisions are we making as individual people, AND collectively as humanity, that creates this world that we live in today?”

And this film does not joke around. The first 10 minutes makes sure you know this story is not going to be warm & fluffy.

We do return to ideas from Totoro but viewed through a more mature lens. We have a forest with a local deity. We have ritual. We have an experience of the sublime.

But we also have disrespect for the spiritual. We have characters who are faced with difficult choices and make bad decisions. And we not only have the celebration of life but the horror of suffering and the reality of death.

In Miyazaki’s eyes thinking of nature as something kind and gentle in need of our protection is not the right way to look at it, because it also places humanity above nature. So in this film, Nature is fierce. It’s big, it’s dangerous, and it does not need your protection.

Princess Mononoke’s characters

The only advantage the humans have in this world is the technology they use for destruction. And this is what we have a conscious choice in today. And so one of the questions posed to the audience becomes, how do you participate in this in your life, today?

Are you going to be like Lady Eboshi and help your own people to a better life, whatever the cost? Or will you be like Jigo and be the company man doing whatever your bosses tell you, washing your hands of whatever the consequences? Or are you going to be like Ashitaka, who has a strong moral compass and always tries to find a balance?

The role of Ashitaka

In this film, Ashitaka is the type of Miyazaki hero who very strongly advocates listening to what each side is saying and then trying to find a way for a balance.

But unlike Nausicaa, who is the same type of hero, Miyazaki is more critical of how Ashitaka does not actually choose a side throughout the film.

Ashitaka wants to save the princess, he wants to save Lady Eboshi, and he wants to save the forest god, and he doesn’t interfere with either of them doing anything. So another question is, would the story have gone down in a different way if he did choose a side?

The historical setting of Princess Mononoke

The film is disguised to take place in a historical setting but like every really good period drama the real period it is talking about is today. And that is behind the very conscious decision to place this film in the Muromachi period of the Fourteen-Hundreds.

Miyazaki was looking for a period in Japanese history that most closely matched the period after World War 2. When huge sweeping changes in society have started, but there is much confusion, and chaotic forces are at battle.

And he chose this period because the questions are the same as after World War Two: should we adapt modern technology and if so, how far should it take over the way we do things now? Are the changes too quick, do we have time to think over what we are losing?

Then we have the question of social inclusion. What groups do we favour? Which groups do we allow into society? Who do we push to the side, who do we accept? Do we give disadvantaged groups a better way to live — like the women employed in the Ironworks who are liberated prostitutes, and the people in bandages that are people living with leprosy? I mention both because both of these facts tend to get censored out of English translations.

(Which is why the information about people living with leprosy existing in the film went around on the internet as breaking news a couple of years ago.)

Characters and motivations

All the characters and forces in Princess Mononoke make choices and act out of those choices, and that creates the conflict. And very much unlike what we’re used to in Disney films and most Western animation aimed at a general audience, characters aren’t 100% right or 100% wrong, 100% good and 100% evil.

Everything is ambivalent. Progress always means letting something go. Choosing one path means that you didn’t choose all the other paths. Favoring one group means that you are not favoring another group. Each character comes with their own ideology, and everyone embodies an inner ambivalence.

The role of the tree spirits (aka. the kodama)

And watching all these events unfold are the Kodama, who are there to be a witness and an audience and they don’t really do anything.

Miyazaki said he put them in because we tend to think about nature preservation as saving nature because it is useful to us. And we should shift our perspective to say that we have to preserve it also when it is not useful, or even because it’s not useful.

The Forest Spirit (aka. the Shishigami)

And this leads us to why is this forest important, and who is the master of this forest?

Like Totoro had Totoro, in this film we have the Forest God or the deer god, the shishigami Miyazaki creates from multiple elements.

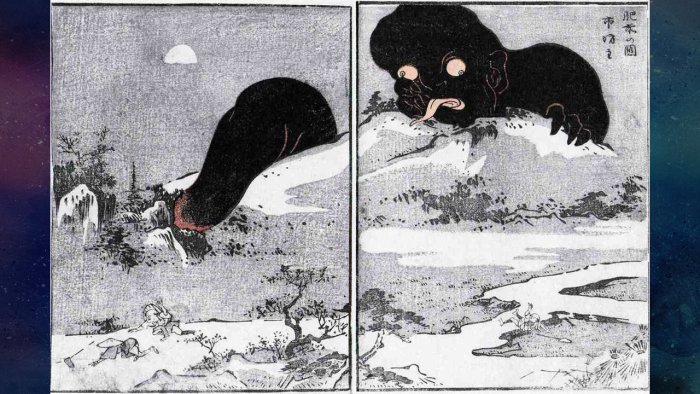

The first is the Daidarabotchi, who are the biggest giants in Japanese folklore, and also sort of a creation god, who are a., very scary, and b., instrumental in forming the Japanese landscape, with its tongue out for good measure.

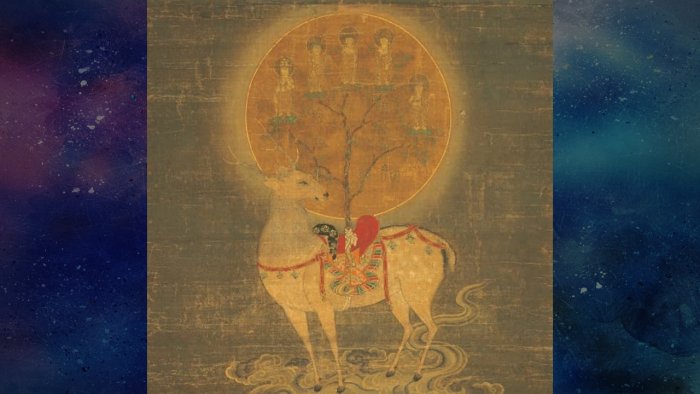

The other source is a widely reproduced Deer Mandala, a mixture of Shinto and Buddhist imagery, from around the historical era that the film takes place in. A deer with a tree growing out of it and reaching the moon, and in the moon you have Shinto deities which are drawn as Buddhas. The iconography calls you to realize your deeper connection to the mystical nature of life, and using that elevate yourself above your existence as an animal to reach spiritual enlightenment.

The Forest Spirit embodies what Romanian religious historian Mircea Eliade calls the mysterium fascinans and mysterium tremendum — being in a sacred space and meeting a god is equal parts awe-inspiring and terrifying at the same time. It’s beyond the human field of experience in every way, and longing for it and fear of it exist at the same time.

So after Totoro helped you learn basic agricultural mythology, all about the cycle of the planting of the seed and the reaping of the produce. Mononoke in turn shows you basic animal mythology. Where each animal group has a central parent animal, and on top of the system is the shamanic Master of the Animals, who is a god figure encompassing animal and human, life and death.

That is an experience of life beyond simple human survival, and the question is: is it worth cutting ourselves off from that experience?

Who is Princess Mononoke?

And with that, we get to the final bit of the puzzle, the titular princess, who drinks blood, leads a revenge attack in the night, feeds the sleeping beauty prince, so she exhibits very non-Disney Princess behaviour.

The significance of Princess Mononoke’s mask

And the key to her is the mask. She is meant to represent something truly ancient, the earliest form of Japanese art, mystical clay figurines used for ritual and religious purposes, dating back anywhere from three hundred BC to twelve thousand BC.

The meaning of ‘mononoke’

But the real question is the name. In the English versions, she is referred to as various things, most often wolf girl, or sometimes wolf-god princess, but in the Japanese original throughout the film she is referred to as Mononoke hime.

So what is this Mononoke? Princess Mononoke makes it sound like that is her name, but that’s not her name, that’s an untranslated Japanese word, so the English title really provides no real frame of reference to understand what this character is about.

So Mononoke does not mean one single thing. It is a group of things. Today there are many separate words for all the different creatures, but at the time the film takes place, they use Mononoke as a group word for all the demons and monsters, weird beings and vengeful spirits — effectively it’s the collective name for all the creatures that belong outside the realm of humans.

So in the eyes of the humans in this film, she is the emissary, she is the representative of the forest gods and spirits. That’s why you have this ancient mask. She is performing the role of the representative.

In essence, the title makes more sense as Princess of the Mononoke. Princess of the Spirits or even the Princess of the Wild which was the film’s title in Hungarian, helps better understand the relationship that San has to this story.

The real question of Princess Mononoke

So the final question of the film is this. Can these people work together, the person who chose to be the representative of natural forces and the person who chose to be the representative of the best that humanity can do?

Can they find harmony between them? Is that enough against the worst that humanity can do? And if it isn’t, how do we move forward from there? Miyazaki tells you some of the answers, but the real big answers are for you to decide.

If you want a deeper look at all of the Studio Ghibli films and the complex mythologies behind them, you’re going to love the Studio Ghibli Secrets guide. Grab it here:

Get the Studio Ghibli Secrets Guide!

Video credits

Written and performed by Adam Dobay

Recorded by Livia Farkas

Editing by Gabi Trost and Eszter Vermes

Special thanks to Flick Beckett and the Duke of York’s cinema staff

Now it’s your turn!

Phew! That was a lot of stuff crammed into 16 minutes. (And it took days of work to pull it back to this ‘shorter’ version!)

What’s your biggest takeaway from this video? Is there something you’d like to hear more of? Let me know in the comments!

Hi Adam!

Reading this gave me more insight to the film but left me more with questions. Considering the story really intends us to come up with the conclusion ourselves, I still wonder which of the characters did the best action. It is easy to point out a person as he/she did the “good” thing, but is it the right path to take as a whole for both the nature and humans now and in the long term. You presented the characters really well and left me searching for more. If ever there is more, I would love to read your critique (as detailed as it can be) on the characters and the decisions they made.

I learned a lot reading your articles / watching your videos. Thank you!

Hi Mei, great comment, there’s definitely a lot there.

In Mononoke Hime, perhaps more than anywhere else, Miyazaki seems intent on setting up scenes and dialogue in a way that forces you to consider every single viewpoint presented. One thing that makes a lot of Japanese storytelling fresh for me is that the moralising base that so much Western storytelling defaults to is completely absent. What I mean is that most contemporary Western storytelling is very eager to set up “here is the protagonist, they are morally right; here is the antagonist, they are morally wrong” systems so the viewer is comfortable in knowing which side to associate themselves with. This has its roots in mediaeval European plays that grew into secular theatre and, as a result, a big chunk of modern Western dramatic storytelling. Japanese storytelling does not have the same background so is less prone to the same kind of moralistic structure.

Mononoke Hime is also free of this, and so the story becomes more of “this is a story where these characters, with these backgrounds, these individual viewpoints and these goals stemming from their individual viewpoints meet up and test their worldviews against each other through their actions, and this is the result”.

So what do we, as viewers, do, when Ashitaka is right in his conviction to argue for a nonviolent solution (but is unable to effectively do anything), San is right to protect the forest (but, without Ashitaka, is on track to lose her humanity and succumb to vengeance), Eboshi is right to protect her people who are society’s outcasts (but her protection comes at the cost of the forest and its sacred inhabitants), and so on and so forth?

This also ties in to the underlying theme of ‘progress’, a recurring Miyazaki theme . Progress for Irontown is demise for the forest. Stability for the forest is loss of protection for the people of Irontown. Ashitaka’s ancient way of life is in stark contrast to where society is going. Human progress seems inevitable, so the question is where we draw the line of progress and what we’re prepared to give up. One could argue there is no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ choice from a Western moral perspective: there are decisions only, with each decision carrying its own consequences.

What a deep aspect to analyse. I’ve made a note of this to definitely turn into a video down the line. Thanks for your suggestion!

Hi Adam!

Wow, that’s it! Indeed watching it for the first time then made me uneasy of the conclusion. No clear protagonist and antagonist, it is real life. It is fascinating how different viewpoints are coming together as they clash to dominate or some wants to coexist. Tackling morality and progress left me searching for answers, so interesting. I learned a lot.

Looking forward to your future videos.

Thank you!

hi, I wanted to ask, where did you get the information on Miyazaki saying the reason why he put in the Kodama (as being that are not necessarily useful)?

Hi Milo, great question! If I recall correctly, it was in one of the interviews published in “Turning Point: 1997-2008”, the second of two collections of various texts by Miyazaki. The wider context for the quote was Miyazaki’s frustrations around how many people interpreted My Neighbour Totoro mainly as a call for natural conservation, both with the idea that nature is something to protect because it is precious and fragile, and with the utilitarian/capitalistic undertone that the reason to protect nature is for its use to humanity. These thoughts are where the creatures portrayed in Mononoke originated, with some parts of nature beautiful, others fierce and dangerous, yet others spiritual and beyond human understanding, and finally some parts that are “just there”. This latter would be the Kodama.

Hope this helps!