Kiki’s Delivery service is 30 years old.

Rewatching it now, though, it couldn’t feel younger or fresher – or more relevant in our ever more turbulent world.

In my newest talk, I explore why that is.

With Kiki’s Delivery Service, writer-director Hayao Miyazaki took a close look at the modern and peculiarly Japanese genre, the “mahou shoujo”, or “magical girl”, and how to use this genre as not only as a vehicle for female empowerment but how to ground the magical girl’s adventure in a peacetime setting where there are no enemies that you need to defeat. Instead, you have to strike a balance between following your calling and serving the society you choose to live in.

In my newest talk that I gave at Kiki’s 30th anniversary screening at the Duke of York’s cinema in Brighton, I explored what makes the film tick and why it’s still relevant after three decades.

In the talk I focus on how Kiki ties in to Japan’s magical girl movement, but also bring up how Kiki’s journey can be interpreted to be about struggling as an artist when you’re young, starting a small business, or even starting over in a new country.

Watch the full video above, and don’t forget to grab your copy of the Studio Ghibli Secrets guide where I reveal the story patterns behind all Studio Ghibli films.

Get the Studio Ghibli Secrets Guide!

Can’t watch the video? Don’t worry, you can read the whole thing by scrolling down. 🙂

And if you want to know what happens at the end of the film in the original that was changed in the American dub, highlight this spoiler-y section below:

About two-thirds into the film, Jiji loses the ability to speak, or, depending on the perspective, Kiki loses the ability to understand him. In the original, Kiki doesn’t regain this ability, signaling that she’s grown up and with that comes the loss of some parts of childhood. The creators of the American dub took the liberty to change the ending of the film by having Jiji speak in a shot during the celebration sequence, making Kiki regain everything she lost during the story.

How Kiki’s Delivery Service grounded the Magical Girl genre – full text

- Where does Kiki’s character originate?

- Why is the ‘magical girl’ so important to Miyazaki?

- Why do so many Japanese artists create stories centered about young magical women?

- How Miyazaki reexamines what the magical girl should be

- Kiki as entrepreneur and expat

- The freedom of flight is not just fun and games

- Growing up as loss

- Multiple endings: differences between the Japanese and the American dub

Hello everyone and welcome to this special anniversary screening of Kiki’s Delivery Service.

Quick show of hands, who’s seen this before? Leave your hand up if this is one of your favourite films? Now leave your hand up if you saw this when it came out in 1989? That is a lot of bonus points.

Okay. I’m Adam Dobay and whenever there’s a Studio Ghibli film here, they throw up a big Totoro signal in the sky and I come running. I have a background in film theory and film translation, and for more than 8 years now I’ve researched storytelling in Japanese animation.

Today I’m here to give a quick introduction to why this film is important and some elements for you to notice as your watching. There will also be a Q&A and discussion afterwards, so if you’d like to stick around and discuss the film, feel free to join me after the screening in the bar upstairs.

There’s also a complimentary guide to the Studio Ghibli films that I created for these screenings, you can get that on my website followthemoonrabbit.com.

So yeah, this film is 30 years old this year, and the real interesting thing about it is that it didn’t age at all. In fact, Kiki’s Delivery Service was so ahead of its time that Western films and especially films for children are still barely catching up with the things Kiki was already saying in 1989.

Because when you look at it, Kiki is about trusting children, and especially young girls, with independence, and making their own decisions when growing up.

You are not only allowed but encouraged to go out into the world, and explore, and find the thing that best fits your abilities.

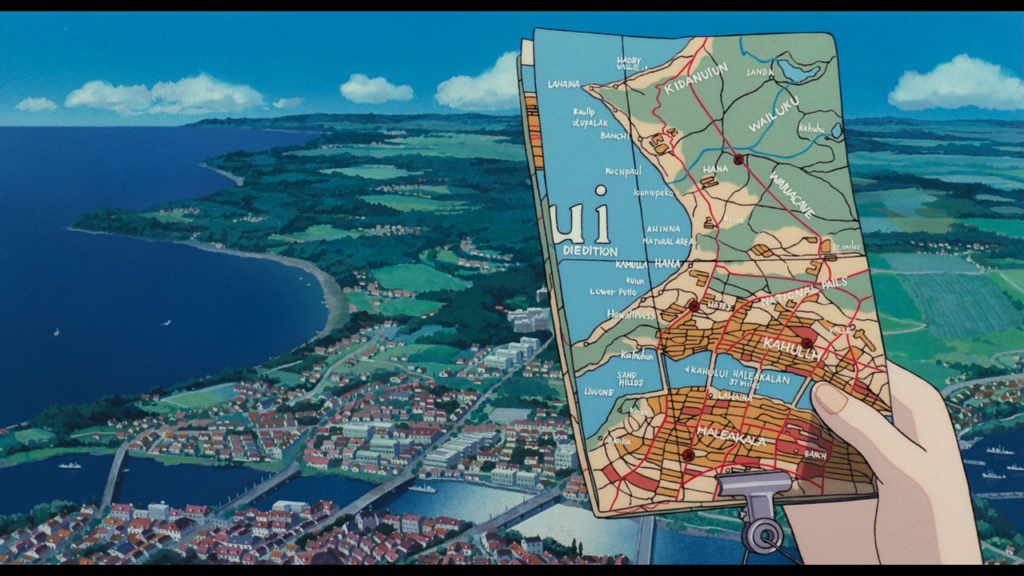

And despite the locales in this film being this seamless mix between French and Italian and German and Swedish architecture, with locations having Hawaiian names, this is a Japanese story at its core, so it sets out to find a balance between you as an individual finding your calling, and then putting that calling into the service of your community.

Where does Kiki’s character originate?

So why is this so important to writer-director Hayao Miyazaki?

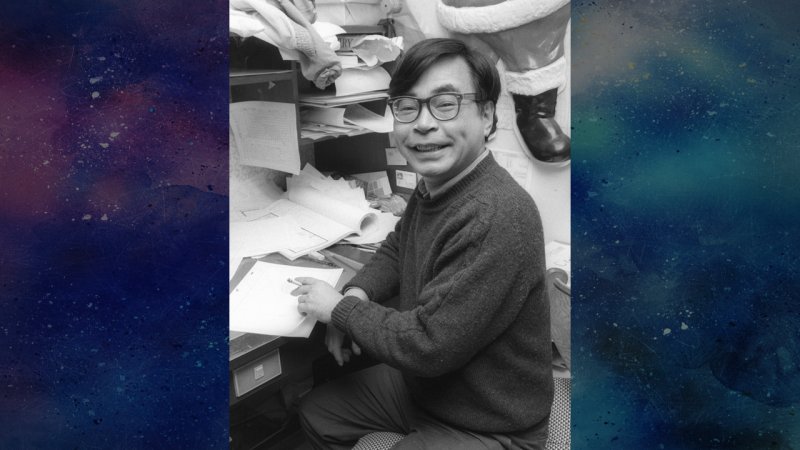

Here he is, 48 years young in 1989. Well, he always likes to look at the problems that his intended audience is facing, and then look at what stories are currently told to that audience.

And in this case, this is the Japanese storytelling genre called the magical girl, or mahou shoujo.

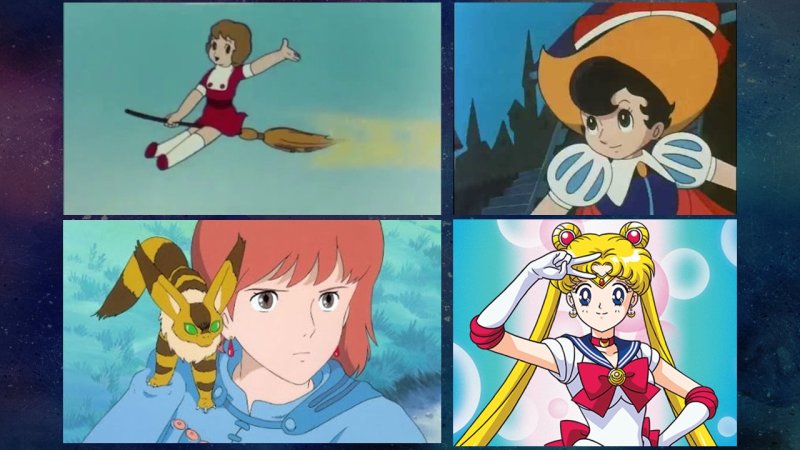

Now Kiki with her flying broom and talking cat, comes from a long line of Japanese witches. Borrowing the Western concepts and visuals of witches without the baggage of Western history, Japanese artists have used these characters to tell new stories about female empowerment for more than 50 years.

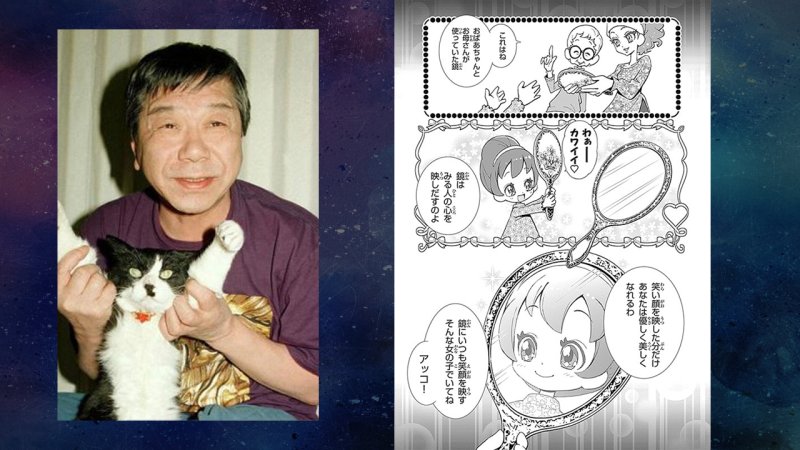

One of the earliest people to do that was Japanese comic artist Fujio Akatsuka, and his probably magical cat. He’s the author of what’s considered to be the first magical girl manga, Himitsu no Akko-chan, The Secrets of Akko-chan, first published in 1962. And the secret is that she gets a magic mirror that she can use to transform into anything.

And this is Osamu Tezuka, amazingly prolific manga artist and one of the founders of modern Japanese animation. And he’s responsible for not only the first prototype of the magical girl, Princess Knight in the fifties, but his was the first animated magical girl series, Mahou Tsukai Sari, or Sally the Witch, in 1966.

Sari provided much of the groundwork for the magical girl genre. She’s ten years old, with an exotic Western style skirt and haircut, and she uses her magical powers in secret to help out with everyday scenarios, like conjuring ice cream for her friends, or summoning a fancy house to play in, or catching the occasional burglar.

Despite Sari’s focus on everyday magic, the series does coincide with second-wave feminism in Japan, and shows some of the new ideals of independence and opportunity that Japanese girls can now aspire to, very different from previous tradition.

Why is the ‘magical girl’ so important to Miyazaki?

And then comes the next generation of animators, where Miyazaki builds and extends on these foundations in his early standout film Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind, which is a must-watch if you haven’t seen it.

In that film he asks, what if the magical girl did more than help out in mischief and things around the house. What if the magical girl was also the hero that saves the world?

Nausicaa was a huge revelation in Japan and created its own genre of world-saving superhero girls that would dominate the nineties and beyond.

Why do so many Japanese artists create stories centered about young magical women?

Well, many of them, especially Tezuka and Miyazaki, and later, people like Naoko Takeuchi, creator of the hugely popular Sailor Moon franchise, are all trying to figure out an answer to, how do we do things differently as a society?

Coming out of World War Two there is a period of soul-searching in Japan, where the main question is:

What can we do so we never again end up with a culture based on oppression, on hierarchy, on violence? How do we encourage a culture built on peace?

And one answer to that is instead of focusing exclusively on the adventures of boys and men who get ahead through fighting, new stories have to be introduced with young, modern girls who solve problems in non-violent ways.

How Miyazaki reexamines what the magical girl should be

So when Miyazaki goes on to adapt the children’s book Kiki’s Delivery Service, he goes back to the roots of the modern Japanese witch and looks at how this character can function as part of a peacetime society.

Which is why there are no enemies in this film. Kiki’s quest is not to defeat some evil being, and it’s not to solve a big problem that she herself has created, like a lot of Western animation does with female heroes.

Kiki’s quest is to figure out her own place in life as someone who has just left childhood behind, and is living the inbetween period between between childhood and adulthood. She has to figure out what she wants to do with her talents that she can also help her community with.

And here’s the twist that Miyazaki introduces. In a lot of early magical girl stories, the magic is about wish fulfillment. You can conjure up fun things to wear and pretend to be an adult with, but at the end of the episode you go back to being a child. You don’t grow.

But in Kiki’s world, magic is a talent like any other, and you have to figure out how to make it work if you want to be able to make money and take care of yourself as an adult.

The film is quite realistic about how in today’s world you have to make money to survive, and there are many scenes focusing on the struggles of living on a tight budget.

Having only one set of clothing will be a constant source of stress for Kiki throughout the film. And if you pay attention at the really short scene at end of the film when Kiki goes back to the shop window she was looking at earlier, you will see what this film wants to tell you about the values it finds important.

Kiki as entrepreneur and expat

So Miyazaki doesn’t sugarcoat growing up. It’s hard to move away from home and try to figure out how to operate in a new society that’s different from where you came from. And that’s okay, because you can also figure it out.

This, incidentally is why the film hits home with a lot of expats all around the world. It perfectly captures this phase of „I’m not there anymore, but I’m not really here yet either.”

Thankfully this is one of those ideal worlds, those small-scale utopias where no one questions a young woman’s right to work, to create, to run her own business.

And she gets a lot of mentorship along the way, too, from the people who’ve done it before her. The artist, the baker and her husband, the old lady, they all bring advice and even investment.

Because Kiki is also about entrepreneurship and figuring out how to make it as an artist or a self-employed person.

There’s scenes about figuring out where there’s a gap in the market. How to get your first customer. What rates you should charge. Dealing with writer’s block. Continuing work even when others are having fun or when the weather is awful.

And this is all hard work, and the film doesn’t shy away from showing you that.

The freedom of flight is not just fun and games

And even though Kiki’s art, what she’s best at, is flying, that’s not all just fun and games either. Miyazaki wrote in his early notes for the film that:

“It is usually felt that the power of flight would liberate one from the earth, but freedom is accompanied by anxiety and loneliness.“

Hayao Miyazaki

So you can watch out for all the times there is flying in this film, and how the emotional context of the flying changes in each scene based on how Kiki is feeling.

Growing up as loss

And finally, this film is about loss. Miyazaki said at one point that classic magical girl stories do not include loss. And that’s wrong, because every time you step into a new era in your life, you gain something but you also leave something behind.

Things are good again after the transition but they will also never be the same as they were. There’s a bit of a melancholy there, and that’s why the film ends as it ends.

Multiple endings: differences between the Japanese and the American dub

At least if you’re watching the original Japanese version. When Disney bought and dubbed this film into English, they were a bit naughty and not only changed the cat’s personality from timid and cautious to sarcastic, but they actually went ahead and changed the ending, regardless of what the original artist intended the film to say.

And the change shows a big difference between mainstream American storytelling and Japanese storytelling.

An American happy ending happens when I have something, then lose it, then get it back again. I will have more in the end than what I started with, otherwise the adventure is considered a failure.

In Japanese storytelling, as you go through your life, you gain and learn new things, but you also let go of things along the way. It is happy and sad at the same time, which I think is more closer to what life actually is like.

But I don’t want to spoil the end of this film, so I’ll only say that the difference is that the talking cat says something at the end of the American version that he does not say in the original Japanese.

There are multiple versions of the dub and they fixed in a later version so even I don’t know which version is going to screen now. In any case, if you have the original at home it’s a good idea to pop the disc in and watch the last two minutes again in the subtitled version. Or you can ask me after the film and I will tell you.

There is so much more to say about Kiki and the other Ghibli films, so if you’d like to learn more you can hop on to my website followthemoonrabbit.com to download my guide to all of the Ghibli films.

Awesome analysis Adam—always love reading and watching your content! Gives me a much deeper appreciation for the themes that at first glance seem more simple and child-focused. when they’re really quite sophisticated and complex.

Thank you! Yeah, I also fell into the trap previously of thinking of Kiki as one of the ‘simpler’ Miyazaki films — only to find how layered this one is as well. This seems to be Miyazaki’s m.o., making elaborately layered works of art so seamless and effortless that the end product feels simple even if it’s not!

In fixing whatever was a bit naughty that Disney did for the original English-language release, they can change back whatever else they want to that dub, but if they take out the Sydney Forest songs that’s not naughty, it’s criminal. The film with her additions is clearly better than the original.