In Howl’s Moving Castle, Hayao Miyazaki flips his own script and instead of making a coming-of-age film, he makes a film-where-people-should-have-come-of-age-but-didn’t, shaping his story around how to grow up if you’re already an adult.

Howl’s Moving Castle is unique in the sense that it’s like a setup for a sitcom: it takes characters that have the same problem – Howl, Sophie, Markl, Calcifer and even the Witch of the Waste are people who don’t want to take responsibility for where they are in their life, and don’t want to move on — essentially they don’t want to grow up.

So Miyazaki literally puts them under one roof, so they can help each other work through their issue.

In the final video in my Introduction to Studio Ghibli Storytelling series, I reveal:

- how Miyazaki seamlessly integrates fairy tale storytelling with archetypal mythology

- the interview quote that sheds some light on the perspective to apply when watching this film

- the big reason why the characters don’t want to grow up and how that ties into Miyazaki’s lifelong anti-war stance

- and how the ending is actually not that weird if you pay attention to how the film sets up its storylines

Watch the video above, read the full transcript below, and don’t forget to grab your copy of the Studio Ghibli Secrets guide where I reveal the story patterns behind the multitude of Studio Ghibli films.

Get the Studio Ghibli Secrets Guide!

Howl’s Moving Castle Analysis: A film about people who don’t want to be adults

- How Miyazaki matures as a director

- Nuanced storytelling and self-referencing

- “In reality, I often forget about the children”

- Coming of age in Miyazaki’s earlier films

- Howl’s Moving Castle – Character Analysis

- Howl’s thematic links to Spirited Away

- The problem with adults in Howl’s Moving Castle

- Forging a new kind of family

- Howl’s path from aggression to pacifism

- Why the ‘weird’ ending of Howl’s Moving Castle isn’t so weird at all

- Miyazaki’s answer to being an adult in a world where adults are otherwise horrible

- Now it’s your turn!

Today’s film is Howl’s Moving Castle, or better known as Part 2 of Miyazaki’s egg trilogy. On a more serious note, today I’d like to talk a bit about how Miyazaki matures as a director and how that reflects in him making a film about adulthood.

I’m Adam Dobay and I’m your host for this series. I come from a background in film theory, I worked for ten years in screenwriting and film translation, and I’ve also done a lot of research into Studio Ghibli, some of which I’ve shared over the past six weeks.

How Miyazaki matures as a director

As with all the other Miyazaki films, there’s a lot of layers to Howl’s Moving Castle. There’s fairy tales and archetypal mythology as well as social and environmental commentary.

The thing is that as Miyazaki matures as a director, his films that were already complex and nuanced to begin with, become even more granular in their complexity.

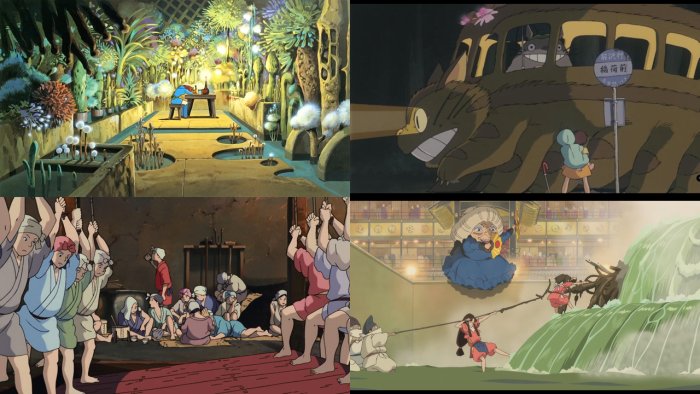

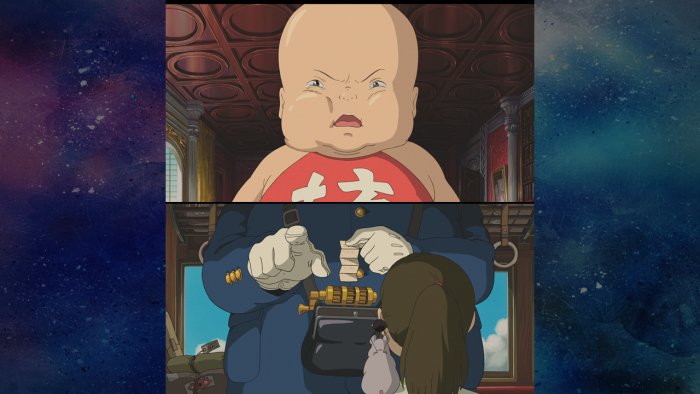

Already you get a sense of this in Spirited Away where there are entire blink-and-you’ll miss it story arcs, like the character development of the baby for example.

Nuanced storytelling and self-referencing

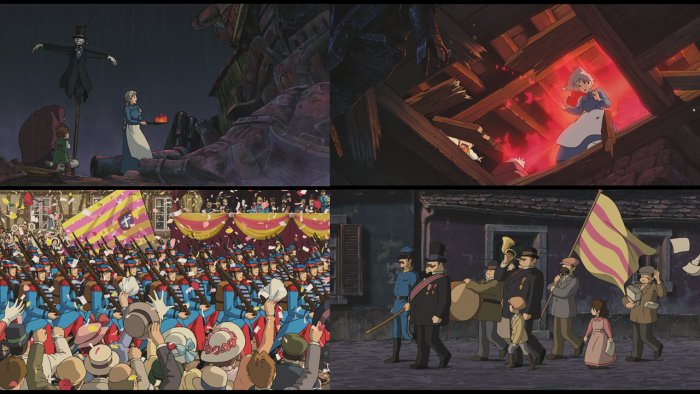

Anyway. A similar thing happens in Howl, where the story has such a frantic pace that you can spot new details of significance with every rewatch. If you’ve seen this film many times, I recommend you look at how Sophie appears different in almost every scene, or all the different metamorphoses the house goes through, or even the caricature that is the war developing in the background.

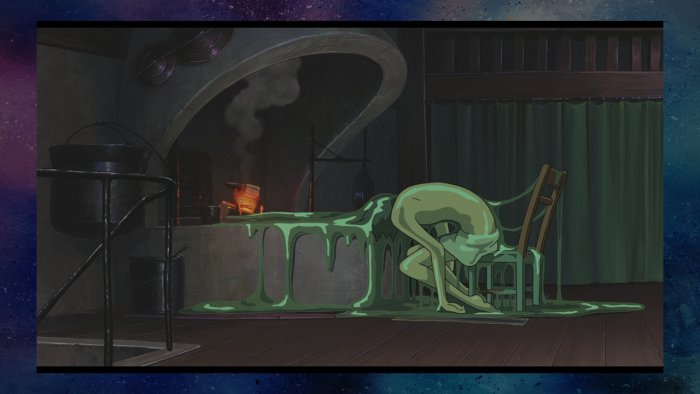

Also, there is this tendency for Miyazaki to start referring back to his earlier films, not as easter eggs, but reusing his own symbols he introduced in earlier films, like the umbrella from Totoro, or the binding slime magic from Spirited Away, or even eating as a metaphor – what you eat, what you regurgitate, what you shouldn’t have eaten, and so on. And you can compare and contrast what these similar elements mean in different contexts.

Of course the great thing about Miyazaki is that all of the layers to the film are neatly wrapped up in strong character-based storytelling which remains the core of the film, so with each subsequent viewing you can either pick one layer of storytelling to focus on, or you can choose to just let the story take you on its journey. So for today I’m just going to pick a couple of threads to look at and will talk about everything else at a later time.

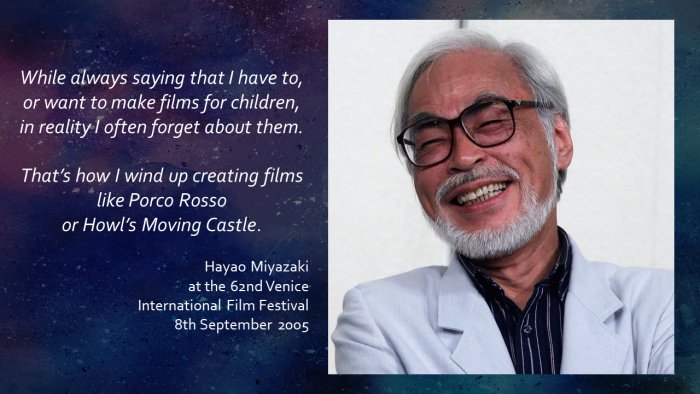

“In reality, I often forget about the children”

That said, here’s a quote from Miyazaki I came across just this week that I think really helps put this film into perspective. He said this on a 2005 press conference at the Venice Film Festival.

Now he did laugh quite a bit after saying that so it’s not one of those quotes you have to take 100% seriously, but it’s still a very interesting thing for him to say in the sense that this film is about adulthood more than other Miyazaki films.

Coming of age in Miyazaki’s earlier films

Most of his earlier films have some sort of coming of age story. Growing up through trying to find a solution to the problems that your parents’ generation has created, like in Nausicaa, or Whisper of the Heart, or Castle in the Sky.

Or growing up by fighting for something and having to experience the loss of what you’re fighting for, like in Princess Mononoke.

Or growing up by finding your place in society and the modern world and making sure you don’t turn into a pig when you grow up.

And after all these coming of age stories we get a film starring people who for are actively trying to avoid adulthood for most of the runtime.

Howl’s Moving Castle – Character Analysis

Sophie Hatter – the girl who leapt through adulthood

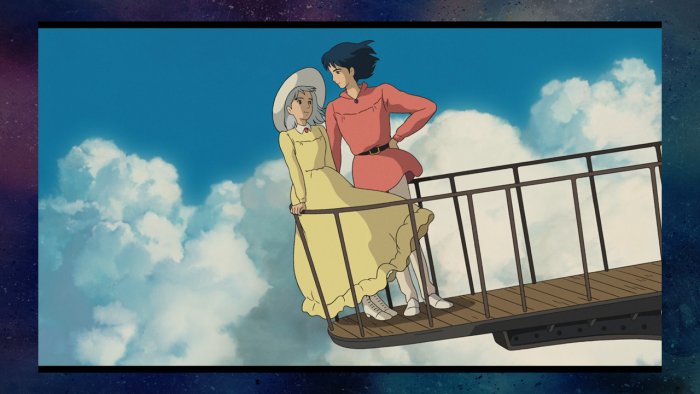

We have Sophie who has a lovely outlook on life at the beginning of the film. Just look at that view. Of course she doesn’t want to live her life in the back room making hats, but her experience is that it’s still better in here than out there – a sentiment that I think the introverts in the audience can empathize with.

So when Sophie gets her „curse” ten minutes after the film starts, it’s actually great for her. She’s actually really quick to embrace it because it means that she can skip this adulting thing entirely and go straight into old age.

Howl – the world’s most powerful adolescent

Then we have Howl who is permanently stuck in adolescence. He loves the power that comes with growing up but not the responsibilities that come with being an adult. Throughout the film, Howl tries to be everything for everyone while being deadly afraid both of losing control and of not being loved.

One of the funniest scenes in the film, which is Howl’s emo breakdown, also reveals something very serious about what this character is really struggling with.

Markl – the boy who had to grow up too fast

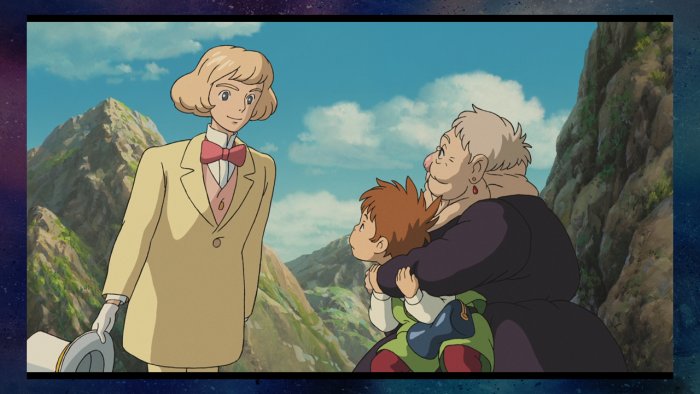

Then we have Markl who we know little about but we can deduce that he’s the kind of person who had to grow up too fast. Pretending to be an adult is his actual job but he shows his true colours as we learn what he really needs is belonging and a family.

Calcifer – the fire demon with an existential crisis

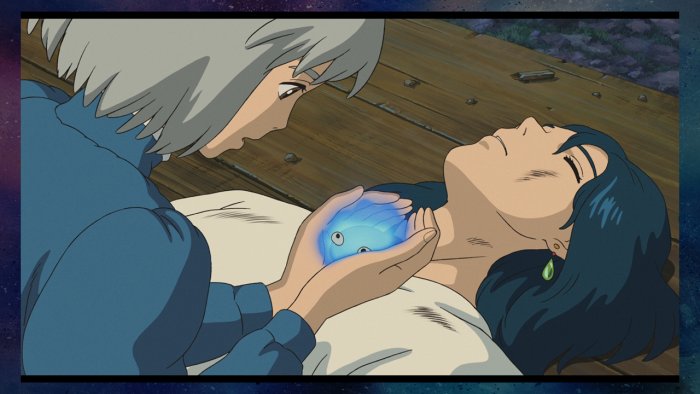

We also have Calcifer, who always takes first place in cutest ancient fire demon competitions. He is actually dealing with the same problem as the other characters, but in a more metaphorical sense: His question is, what happens if I change? Can I change while remaining the same person? If I change, do I die?

Heen – the dog with the blink-and-you’ll-miss-it storyline

And the blink-and-you’ll miss it storyline in this film is the dog with the Muttley cough, who has exactly one decision point in the film that lasts for about two seconds and also involves coming out of dependency and making a stand for something. (See if you can spot it.)

Howl’s Castle as a character in its own right

And before I forget, we have the castle which is a character in its own right. It also changes throughout the film, and its question is the same as Calcifer’s: Do I survive if I keep changing? If I fall apart, can I be put together again? And especially because of this latter question there’s an undertone of the Castle being Japan in a similar way to how the bathhouse in Spirited Away was like Japan.

Throughout the film, the Castle grows, it changes, it suffers, but it survives and all this change is needed for it to grow and to become more of a house that every one of us can live in.

Howl’s thematic links to Spirited Away

By the way, with all these characters dealing with the difference in what I show to the outside world versus how I’m really feeling, there’s again this Japanese separation of the outward facing facade and the inner self, the honne and the tatemae that I mentioned last time with Spirited Away. Even the house has its context-dependent outward faces and its inner faces.

So the question is, why are these people trying to avoid adulthood? Well, because of what adults are like.

The problem with adults in Howl’s Moving Castle

And in this film, adults are greedy, egotistic, chase money or fame or glory, they fight wars or have power struggles, manipulate each other.

The examples of adults Sophie sees around her are her colleagues, who are super shallow and gossip about having a better life but never actually doing anything about it…

She has her sister, Lettie, whose entire life revolves around looking pretty and pleasing men in return for attention.

And she has her mother, whose personality is in constant competition with her hats for who is more over the top.

And look at the men in Sophie’s life: lovely people. Just in the first five minutes you have street harassment, catcalling (or mousecalling more specifically) and every scene with women on their own has men intruding.

If this is what being an adult is like, no wonder you want to skip it, and no wonder you go with the first David Bowie Lookalike Competition Runner-Up that comes along. With of course the first prize of the David Bowie Lookalike competition going to Ponyo’s Dad.

And then there’s Howl’s adults. Suliman, a corrupt mother figure, the king, an idiot father figure, the Witch of the Waste, who’s only in the magic business for greed, and the other wizards who did what they were told to do and lost themselves entirely.

But the point the film makes is that while all adults are horrible in their own special way, all these coping mechanisms to avoid becoming an adult do not work. Escapism does not work. Whatever magic the characters use to hide the truth, the truth is there underneath and if not addressed, it will lead to disaster. They have to figure out how to become adults in a way that they stay true to themselves.

Forging a new kind of family

Miyazaki wants his characters to live their true lives and find their true spirits, so the path of the characters is to help each other realise that they need to be their true selves. They basically have to become each others’ therapists.

Howl’s path from aggression to pacifism

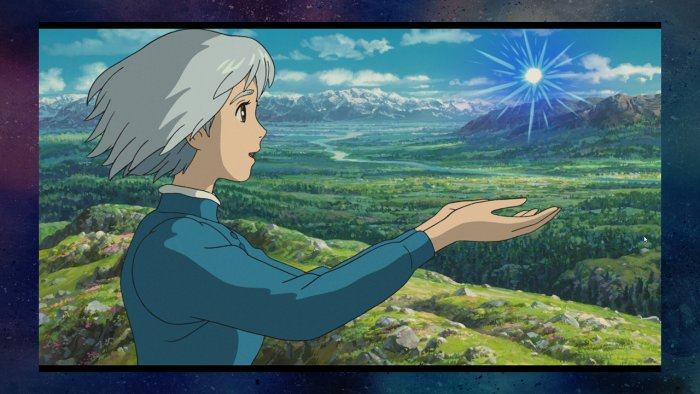

And the story thread this is most expressed with is Howl, who lives in the delusion that he can solve everything with careful maneuvering, but as the film progresses, he starts to get ground up by his many roles.

Like some of the other Miyazaki male heroes, his character arc is to learn how to solve things without aggression and how destruction is also self-destruction.

And of all the male Miyazaki heroes, his learning curve is the steepest, because for most of the film he actively embraces violence. He says, it’s okay, I can solve this whole war thing alone, don’t worry about it. I’m not gonna be like those other guys. They’re the bad guys with magic. I’m the good guy with magic.

The problem is that it doesn’t work. You can’t solve war by winning, even if you’re the best at it. Miyazaki’s bottom line is always that no war is worth fighting. Note the use of fire in this film. Fire is good if you use it in moderation, as the core energy to heat, to cook, to keep your castle moving. But if you have too much of it, it will be destructive fire and it will consume everything you love.

It’s a downward spiral that needs to be stopped, and that’s why Sophie needs to figure out how she can get to the core of who Howl is underneath that fire, and how she can bring that back.

Why the ‘weird’ ending of Howl’s Moving Castle isn’t so weird at all

And that leads us to the ending, which is one of the more weirder Miyazaki endings. I’ve often heard it criticised because as we get to the end of the film everything is resolved quite suddenly, but if you watch the film close enough and see its internal logic, the entire story was really a setup to this ending.

And what Miyazaki does to achieve this is that he combines fairy tale rules with therapy rules. In fairy tales, you find the point of the main plot, solve it, and the kingdom is magically restored. In therapy, you get down to the core of the problem, crack it, get your breakthrough moment, and the deeper the change is, the bigger the ripple effect it then has on your life.

And that is what happens at the end of the film. People find their true hearts, literally, and what was misplaced is replaced, literally. The violence stops because the need for the thing that was substituted with violence was fulfilled, and there’s no need for violence anymore. Which, in itself, is quite a strong commentary on the reasons for war and how to avoid it.

Miyazaki’s answer to being an adult in a world where adults are otherwise horrible

But the real statement is how the choice is not between becoming a horrible adult or not growing up at all. The resolution comes when the characters can learn to define for themselves what adulthood is, what community is, what family is, and what is worth making a stand for and making and effort for. And that is the kind of adult Miyazaki would like you to be. And he’s asking very politely so you should at least try it out.

Again there’s many other things to talk about, like how the house follows Freudian dream analysis rules, or how the concepts of eating and regurgitating things you should not have eaten are revisited, but those I’ll leave for another time.

These are your pointers for today. Closing off, I’d like to thank you for coming to at least one of the six screenings, and I hope that you liked these intros. If you missed any, you can hop over to my website followthemoonrabbit.com where I have published all of this introductory talk series.

Get the Studio Ghibli Secrets Guide!

Video credits & acknowledgments

Written and performed by Adam Dobay

Recorded by Livia Farkas

Editing by Gabi Trost and Eszter Vermes

Special thanks to Flick Beckett, Picturehouse Cinemas and the Duke of York’s cinema staff.

Howl’s Moving Castle ©Studio Ghibli, 2003.

Spirited Away ©Studio Ghibli, 2001.

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind ©Studio Ghibli, 1984.

Princess Mononoke ©Studio Ghibli, 1997.

Ponyo ©Studio Ghibli, 2008.

My Neighbor Totoro ©Studio Ghibli, 1988.

Now it’s your turn!

What’s your biggest takeaway from this video? Is there something you’d like to hear more of? Let me know in the comments!

Hi Adam, Congratulations for your beautiful blog. Thank you for your dedication and for sharing your knowledge.

I am a Colombian journalist in Tokyo doing research on Hundred Years of Solitude, G Garcia Marquez´s novel, and found many visual connections between the book and Miyazaki´s films. I wonder if there is any study of research that connects “magical realism” to Studio Ghibli´s productions.

Thank you, GR

Hi Gonzalo, thanks for writing in!

Definitely the way that Miyazaki’s worldbuilding almost always ends up in story universes where fantastical elements appear in a very matter-of-fact way and are not remarked as anything outstanding or out-of-the-ordinary, I’d say that Miyazaki’s storytelling has much in common with magical realism (although I know the term is very fluid and can change from author to author). I’d love to read more about Miyazaki’s work analysed through a magical realist lens, and I wonder if there’s been a study exploring it before. I can’t think of anything offhand other than Gabrielle Bellot’s 2016 article on LitHub https://lithub.com/the-magic-of-miyazakis-literary-imagination/

Good luck with the rest of your research, and definitely if you decide to write any of this up.

Hi Adam,

Thank you very much for writing such a nice article. I just randomly found it but I really enjoyed reading the whole thing. Howl’s moving castle has always been my favourite Miyazaki movie – though I wasn’t even quite sure why (I also haven’t seen it in a long while). But reading your take on the shown problems and what it’s about, has given me some insight on what I couldn’t put to words on my own. Keep on doing great work 🙂

– Jacky

Hi Jacky, Thanks for taking the time to comment! I also find that these deep dives into films I like give me that much more of an appreciation for them. Anything else in Howl you’d be interested to learn about? I’ll make a note for upcoming pieces of content 🙂

Thanks to the pandemic, I finally rewatched Howl’s Moving Castle. Last time I saw it I must have been 11 or 12, didn’t remember much. This time though, I was really in awe and rewatched it 4 times in a row. Couldn’t believe there’s so much to uncover with multiple viewings, in an anime film above all else. The points you mentioned here are so valuable to understanding/appreciating it more. Heck, if you wrote a deeper analysis essay and made it available for purchase, I’d buy it in a heartbeat.

P.S. the ‘of course you’d go with the first Bowie lookalike runner-up’ made me chuckle. Indeed, that’s what I’d do haha.

Thanks for sharing your interpretation, you’ve suggested some interesting insights into the story. Gave you based them purely on Miyazaki’s interpretation of Diane Wynne Jones’ book, or did you consider the original story as well.

I saw the movie first and then came across the unabridged audio book on Audible, narrated most delightfully by Kristin Atherton and found so much more detail and nuances as well as the inevitable differences in plot. I can highly recommend it.

Something I picked up was that the characters are not outright good or bad, likeable or unlikable, true or dishonest, competent or inept. Rather they sometimes do something clever and sometimes make a mistake; sometimes they act with emotional maturity and the next a covered up insecurity is revealed. And yet despite it all they’re still endearing. Which is more true to real life. We constantly get these messages in stories as well as in our society that we need to perform perfectly and that mistakes will tarnish our reputation and people won’t like us very much if we show our vulnerabilities, which is not the case at all.

Hi Adam,

First of, I want to say thank you for writing this amazing blog. I certainly learned quite a lot of things that I missed in the movie. One question though: Does Miyazaki criticise or condone war and power in Howl’s Moving Castle? Once again, thank you for the hard-work, time and dedication you have put into this.

Kind Regards

Abi

Hey Abi,

Wow, that question could be the base of an entire thesis — or, well, his general stance on political warmongering and pacifist activism could be. In Howl especially, we know from interviews that Miyazaki was very critical of the US/UK invasion of Iraq of 2003 and that added an extra layer to his Howl’s Moving Castle adaptation, the original work not having this storyline at all, instead having the Witch of the Waste and the disappearance of Prince Justin much more central to the plot.

So Miyazaki shifted the story to tackle the carelessness that people go into war more directly than he perhaps did in earlier films — as time goes on, Miyazaki himself gets closer and closer to portraying actual war instead of the war happening off-screen or a long time ago (like in early works Nausicaä or Castle in the Sky where wars happened up to a thousand years ago, while Porco Rosso also takes place in the aftermath of war).

And this becomes central to Howl’s character as well, his character development becoming partly about learning that any participation in war is bad, and you can’t “get out” of a war unscathed once you’ve decided to participate in it — see Howl’s gradual turning into a monster as an allegory for this. Miyazaki concludes that there is no engagement in war that will not escalate the violence, instead doing the right thing is to work on deescalation.

Which is how you get the ending, where the main cause of the war (the disappearance of the Prince) is revealed, and suddenly there is no point in continuing the war. Miyazaki’s point, however fairy-tale the ending is, that wars are not solved by someone winning — it’s by taking away the cause to wage war in the first place.

Hey! Thank you so much for this amazing blog post! I love love this movie, ever since it was first released and I just re-watched it yesterday, so I had to come to the internet to read more about it! I always felt like this movie carried so many deeper messages than the ones I could grasp by myself and this guide really helped me see it better.

I really liked how you explained how each character represents a difficulty humans have regarding adulthood, and now I know why I like Sophie and Howl so much hahah I also totally agree that each time you watch this movie you’ll notice more and more details, like I did yesterday. And I also feel that how you perceive this movie changes SO MUCH according to the age you are! When I first watched it I was a kid, and I thought it was a whimsical fantasy movie, focused on the magic and their romance. Now, as a young adult (while I’m still amazed by the fantasy aspect of the story) I relate so much more to the character personalities, struggles, and development archs.

In summary, I really enjoyed this post, and I’m subscribing to the mailing list. Will definitely read more of your posts, it’s amazing to read the opinion of someone that studied the subject. Thank you!

I love your in-depth analysis of Howl’s Moving Castle!

I think I’ll have a better understanding of the movie when I rewtach it again.

I’m taking an English class turned philosophy class in College this semester and my ENGLISH professor unfortunately (just joking) really loves Plato. We started a project where we choose a movie and apply Plato’s ideas to the movie. I’ll be honest I haven’t got a clue what Plato is saying. 😅 I do! I do in a sense get what he’s sayin but I chose Howl’s Moving Castle as my movie so as you might imagine I’ve had a hard time keeping my thoughts organized when it comes to Plato and now I’ve chosen a movie that is known for being a little chaotic, which means I’m having a hard time getting all of my thoughts in order and then putting these two together has really been a great time (sarcasm). Your article has helped IMMENSELY! I really couldn’t even begin to write about how these two might go together but the way you all sorted this out has really helped me understand the movie a bit more. I’ve always been more of a maths person so English plus Philosophy is a bit of a weakness for me. I like facts, I’m not so great at “musings”. So all in all I just wanted to let you know that this project was looking very daunting fo r me and you’ve really come to the rescue. THANK YOU to you and your team!!

Beautiful in every way. Thank you for helping me see a world filled with so much to love and learn. You swept me away. Thank you